Through Running over the LNER and GWR Systems

FAMOUS TRAINS - 43

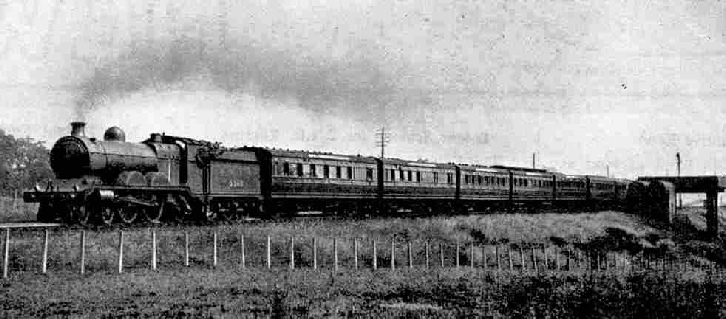

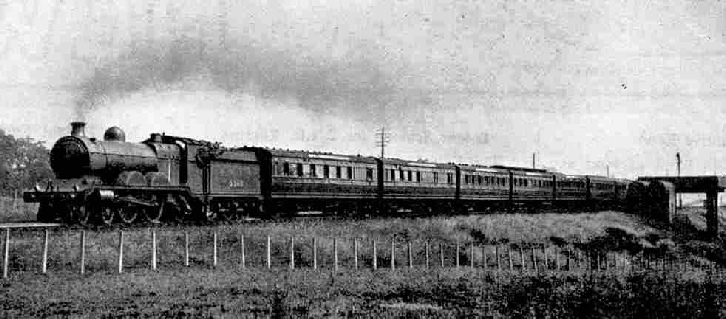

Over the Banbury-Barry portion of its run, the “Ports-to-Ports” Express is headed by one of the G.W.R. 2-6-0 “Moguls”.

IT may fairly be claimed that the late Great Central Railway, now part of the London and North Eastern system, in prewar days did more than any other British railway to popularise comfortable cross-country travel. It was in 1899 that the “London Extension” of the Old Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Company was opened through from Annesley, north of Nottingham, to Marylebone Terminus in London. Three years later followed the opening of the short spur line from Woodford and Hinton, on this extension, to Banbury, on the Great Western main line from London to the North, Although the length of this spur, between Culworth Junction and Banbury Junction, is only miles, it has had a far-reaching effect on the development of British cross-country communications.

Attention was first directed to Bournemouth, and a through service was established in 1902 between the popular South Coast resort and Newcastle-on-Tyne, the North Eastern and London and South Western Railways being associated in the venture with the Great Central and Great Western. The route from the south was over the South Western line to Basingstoke; then the Great Western to Reading and by the West Curve there on to the Bristol main line, whence the route lay through Didcot to Oxford and Banbury. Here the Great Central took over and ran the train through Leicester, Nottingham and Sheffield to York, where the North Eastern took charge for the remainder of the journey.

Since that date many other similar services have been established over this valuable Woodford-Banbury connecting link. One of them follows much the same route between Southampton (where important steamer connections are made) and Newcastle, with through coaches running on beyond Newcastle to Edinburgh and Glasgow. In the summer the main restaurant car part of this train is diverted from York to Scarborough instead of Newcastle, and it becomes a popular “de luxe” service between the Midland cities of Leicester, Nottingham and Sheffield to that famous resort.

But the most spectacular of these through runs is that of the Aberdeen-Penzance train, established after the grouping to show what railway amalgamation really could do in this direction. There is rather a “catch” here, however, as this is not, like the others, a through train; it is only a single through coach. It comes down from Aberdeen to Edinburgh on the ordinary 9.50 a.m. express, there to be attached to the 1.50 p.m. London express as far as York. At York a train is made up with this coach, another from Glasgow to Swindon, various vans and a restaurant car, for the journey to Swindon, over the same route as before through Woodford and Banbury to Oxford, and then round Didcot West Curve on to the Bristol main line. At Swindon the Penzance coach is attached to the night “sleeper” from Paddington to Penzance, and passengers who desire are able to transfer into the Great Western sleeping cars.

So you must not think of the “Aberdeen-Penzance Express” as being a through restaurant and sleeping car express over the whole distance, though the one through coach does have sleeping or restaurant cars in its immediate company for the complete journey in both directions, in the ingenious manner that I have described. Nor must you imagine that such a service as this is established for the sole benefit of through passengers from Aberdeen to Penzance, or vice versa. I often wonder, indeed, if such a ticket as this is ever issued at all, except, possibly, to the seeker after sensation.

No; the value of such a through train as this, as indeed with the others I mention, is in the facilities they afford to the inter- mediate places on the route. The Aberdeen-Penzance coach is generally well filled with people from Aberdeen, Dundee or Edinburgh to Sheffield, Nottingham and Leicester; and at these Midland towns there join the passengers wanting to travel to Plymouth, Penzance and other places in the West Country. Enormous quantities of parcels, too, benefit by the express service that these through trains afford in obtaining quicker overnight transit, and to this express in particular a whole string of through parcel vans is always attached.

This has been a lengthy preamble to my subject matter proper; but I wanted to begin by explaining both the origin and the purpose of these cross-country trains, which to-day form so valuable a part of our express train services. The “Ports-to-Ports” express was another early institution of the Great Central Railway, over the Wood ford-Banbury spur, in conjunction with the North Eastern and Great Western Companies. It began to run in 1906. and was designed to connect the ports of the North-East Coast of England with those in South Wales, entailing a diagonal course across the country from north-east to south-west. The main portion of the train normally runs between Newcastle-on-Tyne and Barry, just outside Cardiff. Sunderland passengers make their connection at Newcastle, and those from West Hartlepool, Stockton and Middlesbrough - the Tees-side ports - at Northallerton. At Sheffield is attached a coach that has come from Hull, so that Tyne, Wear, Tees and Humber are all served at this end of the journey.

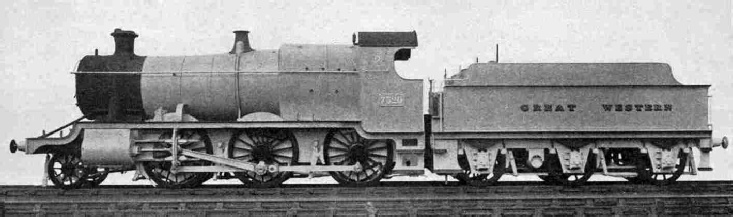

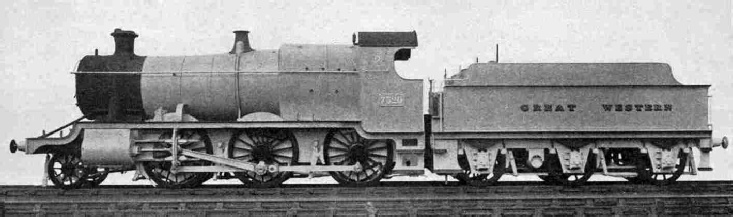

L.N.E.R. Two-Cylinder “V” Class “Atlantic” locomotive No. 705 at York. An engine of this Class, or the similar 3-cylinder Class “Z”, is frequently used to haul the “Ports-to-Ports” Express over the Newcastle to York section of its journey.

At the other end the train stops at Newport and Cardiff, from which, as just mentioned, it runs into Barry. During the summer months, however, other South Wales ports are linked up, for the express runs on from Barry through the Vale of Glamorgan to join the South Wales main line again at Bridgend, whence it calls at Port Talbot and Neath, and terminates at Swansea. Over the route followed between Cardiff and Bridgend this is the only express train ever seen, but still more singular is the link that is used between Banbury and the Severn Valley. This is a sleepy single-line branch running across from King’s Sutton, just south of Banbury, through Chipping Norton, Stow-on-the-Wold and Bourton-on-the-Water - the very names give away the character of the country traversed! - toCheltenham. Here again, of course, the “Ports-to-Ports” expresses in each direction provide a striking variation of the two- or three-coach trains or rail-motors, or occasional freight trains, that are the only other types ever seen on the branch.

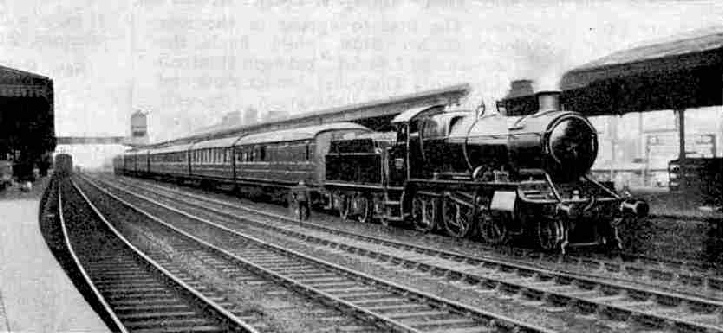

And now the time has come to make the trip. You can have your choice of rolling stock, as the London and North Eastern Railway provide the train one day and the Great Western the next. The L.N.E.R. train travels south on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, returning on the alternate days; while the opposite workings are carried out by the Great Western train. You can easily remember the order, as each train is in its own home territory over the week-end. The G.W.R. usually make up the train with a composite restaurant car in the centre, flanked by composite coaches on both sides and third-class brakes outside them, together with a composite brake for Hull, all of the latest 60 ft, steel-panelled stock.

The L.N.E.R. use a third-class brake, a third corridor, an open third-class coach for diners, a combined kitchen and dining car and a first-class brake, with an additional composite brake to and from Hull, all of the newest East Coast stock. The complete Great Western train scales 184 tons empty, but the L.N.E.R. stock is heavier, the weight in this case being 202 tons. These are minimum formations, and for a considerable part of the year additional third-class coaches are added as required. In both directions north of York, too, extra coaches are attached for the local passengers between York, Darlington and Newcastle.

As we are to be in charge of the London and North Eastern Railway for the major part of the journey, we may as well start at the Newcastle end. We will assume, however, that this is a day on which the train is being worked in the south-bound direction with Great Western stock, as on these days three railways are represented in the formation of the train at the start. Next the engine are two L.M.S. corridor coaches for Bristol, concerning which I shall have something of particular interest to say presently. Then follows our Barry portion of five or six Great Western coaches. The tail of the train is brought up by four non-corridor North Eastern Area coaches of the L.N.E.R., for the use of local passengers as far as York. It only needs some Southern stock to complete the representation of the “Big Four”, and you might have seen even that 90 minutes earlier, on the 8.0 a.m. London express, which went out with L.M.S., Southern and L.N.E, coaches in its makeup!

The engine out of Newcastle may be one of the 50 three-cylinder “Z” class “Atlantics” of the late North Eastern Railway (or possibly one of the very similar 20 “V” class engines, with two cylinders); or, more usually now, a Gresley “Pacific” will undertake the haulage as far as York. Such a train as this is a playtime task for a “Pacific”, as it only weighs about 350 tons all told, and the intermediate timings are very easy. Leaving Newcastle at 9.30 a.m., we are allowed 24 minutes for the 14¼ miles to Durham, with some steep gradients on the way. Then for the 22 miles to Darlington the schedule is 31 minutes; for the 14 miles on to Northallerton 18 minutes, and for the 30 miles thence to York 39 minutes.

Chepstow Bridge over the River Wye. This bridge was built by I. K. Brunel in 1852 and is an interesting early example of the employment of continuous girders.

Thus five minutes over two hours for the 80 miles from Newcastle to York, stops included, is very moderate going; but it is customary with these cross-country trains to allow ample margins of time, as seriously late running may put train services out of gear all over the country. Liberal running times allow a good chance of recovering lost time, as I once proved on this very train, when a “Z” class “Atlantic” ran the 30 miles from Northallerton to York in 30 min, 50 sec., thereby gaining over eight minutes on this short stretch alone. On this occasion we touched 75 miles an hour on a dead level track at Alne.

At York, where we run to No. 14 platform, outside the wall of the station, a fresh engine is waiting to take us to Sheffield. A variety of locomotives is employed between York and Sheffield, and we may have a North Eastern “Z” or “V” class “Atlantic”; a 4-4-0 of class “R” or “R.1”, or a three-cylinder 4-4-0 “Shire”; or, as seen here, a rebuilt Great Central 4-4-0 of the type next in size below the “Directors”. The allowance of 65 minutes for this next length of 46¾ miles is none too easy, as there are some steep gradients, and it is infested with bad slacks for curves, and on account of colliery subsidences.

To Ferrybridge, near Pontefract, the lines are those of the old North Eastern; then, to near Mexborough, we run over the track of the Swinton and Knottingley Joint Railway, first built jointly by the North Eastern and Midland Railways, and now joint L.N.E. and L.M.S. Property. This forms a link of equal importance with that from Woodford to Banbury in maintaining these through train services between the North-East and the South and West of the British Isles.

We leave York at 11.45 a.m. for the longest non-stop run of the whole journey. The going is level past Church Fenton and Milford Junction - in early days one of the most important railway junctions in the North of England, but now no longer a passenger station - to Ferrybridge and Pontefract, but we may have to slow severely in order to cross from one set of tracks to the other at Church Fenton. At Burton Salmon we slow again to diverge to the left from the old York and North Midland line (which proceeds to Normanton), pass through a short tunnel, and then over a fine girder bridge spanning the River Aire. To the left of the embankment running from here down to Ferrybridge we get a splendid view of one of the vast new power-stations that have been erected in connection with the great scheme by which the country is now being supplied with electricity.

From Ferrybridge past Pontefract - famous for liquorice - we mount for 2¾ miles at 1 in 153, drop sharply to Ackworth and mount again for two miles at 1 in 151; then, after some further steep undulations, we drop at 1 in 149-159 for 3¼ miles from Frickley past Moorthorpe, very likely reaching the 70-miles-an-hour mark, if the driver be so minded. The numberless railways that cross us or join us between Church Fenton and Sheffield are in themselves an interesting geographical study, but we have not time to pursue it. Among others, the L.N.E.R. main line from Leeds to London is spanned near Moorthorpe, and if we are lucky we shall catch a glimpse as we pass of the “West Riding Pullman”, flying Londonward at 75 miles an hour or more, as it is now just due.

Presently we see the Midland main line of the L.M.S. nearing us on the right, as we cross the Dearne Valley. We are now slackened severely at Dearne Junction, and we run down to join the Great Central line coming from the Barnsley direction and Wath marshalling yard towards Doncaster. Even worse is to come, as less than a mile later we leave this line to travel round what must be one of the very sharpest curves on any main line in Great Britain.

This is known as Mexborough West Curve, and it turns our train through considerably more than a right-angle in a quarter of-a mile of distance. For this we have to come down to a walking pace. From here to Sheffield, too, there is a constant succession of curves, many of them requiring special speed restrictions; and a general speed limit of 30 miles an hour is enforced for the whole distance. A point of interest just beyond Rotherham is that we run for some distance right alongside the great steelworks of the firm appropriately named Steel, Peech and Tozer.

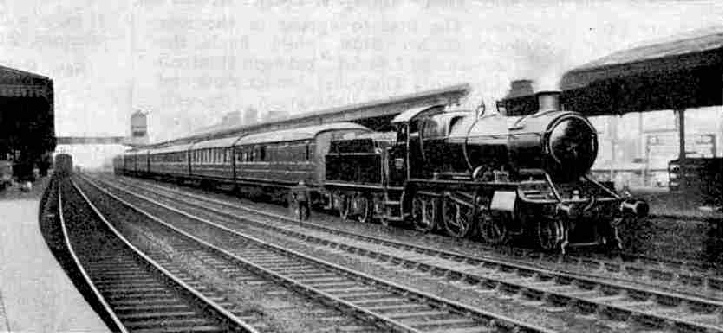

The South-bound “Ports-to-Ports” express leaving York for Sheffield, L.N.E.R.

Sheffield is reached at 12.50 p.m., and if we are to time we shall just see the disappearing tail of the “North Country Continental” by which we travelled so recently, on its way to Liverpool. It is always rather a mystery to me why these two trains cannot be made to connect, as they would give an excellent “all-L.N.E.” service from Newcastle and York to Manchester and Liverpool; and it is tantalising to see that such a connection is possible and yet be unable to take advantage of it.

We are to reverse in the Victoria Station at Sheffield, and as we run in we see our engine waiting for the next stage of the journey, with our through coach from Hull already attached. The engine will almost certainly be one of the handsome Great Central “Atlantics”, which did such excellent service on the London trains - and on some of them, indeed, still do it - and will take us as far as Leicester.

We have already travelled between Sheffield and Woodford, only in the reverse direction, when we had our run on the “3.20 Down Manchester”, that not much need be said about this section of the journey. Between Sheffield and Nottingham we shall probably take our lunch, and at the same time remark the singular fact that lunch on this express costs a different amount on different days. If it is the Great Western train, you may have the excellent two-course lunch served by that company for a modest half-crown; but if it is the London and North Eastern train the usual five-course meal will be served at 3s. 6d.

Leaving Sheffield at 1 p.m. precisely, we set out over the 38¼ miles to Nottingham. Rising at 1 in 144-155 past Darnall to the summit - once in tunnel, but now opened out to a four-track cutting - we drop sharply to Woodhouse, and reduce speed over the junction. At Eckington we pass over the second set of track water-troughs that we shall see on this journey. From Eckington there is a severe rise of 9½ miles past Heath to Pilsley, the first four miles from Staveley being at 1 in 100. After this we encounter sharp undulations to Kirkby South Junction, and then a long and practically unbroken downhill at 1 in 132, where again we shall probably touch 70 an hour or more, to Nottingham. It is interesting, just after Annesley Sidings, to see on the right the old Great Northern and Midland lines running exactly parallel with ours, a brief width of fields separating all three, until below Linby we curve to the right and cross the other two. The approach to Nottingham Victoria Station is made slowly through two tunnels, and we are due there at 1.51 p.m.

From Nottingham to Leicester is the fastest booking of the journey, 27 minutes being allowed for the 23½ miles, which requires an average of 52.2 miles per hour. In earlier days the northbound “Ports-to-Ports” was only allowed 24 minutes for the same distance, but the time is now eased out to 26 minutes. About seven minutes after leaving Leicester, by the way, we should pass the latter express, in full cry northward. We are due away from Nottingham at 1.55 p.m. Touching 60 miles an hour at Ruddington, we fall to between 50 and 55 at Barnston Summit; dash down to Loughborough at over 70; climb to Rothley, and finish smartly into Leicester at 2.22 p.m. The interest of this last station lies in the fact that it is one of the biggest in the country built on the “island platform” principle. The one main platform, with the up line on one side and the down on the other, is 1,245 ft. in length.

There is probably a change of engines here, and for the next stretch to Banbury we get either a fresh “Atlantic” or possibly one of the big four-cylinder 4-6-0 engines with driving wheels of reduced diameter for mixed traffic work. We are away from Leicester at 2.28 p.m. on the short run of 20 miles to Rugby. Although we have over seven up miles at 1 in 176 past Whetstone and Ashby to negotiate, the timing of 26 minutes is easily kept.

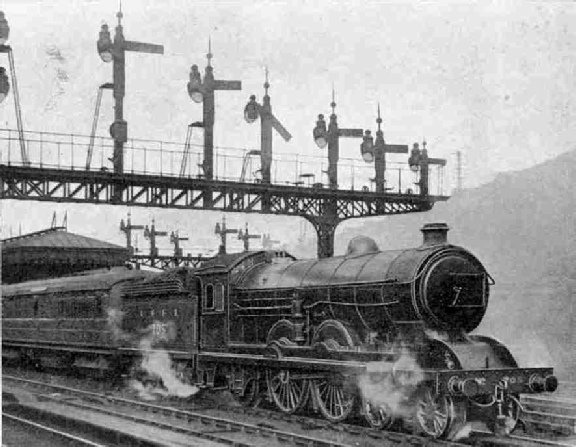

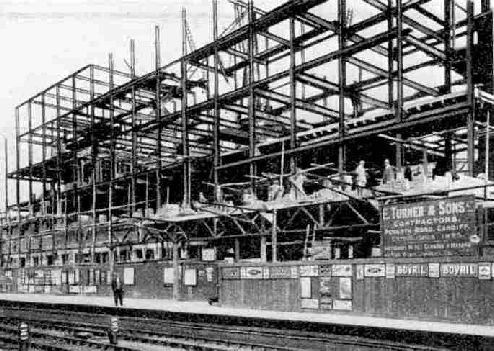

Newport Station in course of reconstruction by the Great Western Railway Company.

Then follows the final L.N.E.R. stage of 25½ miles to Banbury, allowed 35 minutes - again an easy piece of work. We climb the seven miles of 1 in 176 from Braunston to Charwelton, threading the two miles of Catesby Tunnel on the way, and then taking water from the third and last set of L.N.E.R. track-troughs. After passing Woodford Junction we slow over Culworth Junction, diverging to the right from the London main line; achieve some more fast running on the four-mile descent towards Banbury; clear Banbury Junction, and draw up in the Great Western Station there at 2.55 p.m.

Here we may be surprised at the type of engine that is awaiting us. It is none other than one of those handy and very numerous Great Western “Moguls” - a “maid-of-all-work” class, if ever there were one. Over the next section of our journey there are various bridges that can carry only certain maximum weights, and the “Moguls” are in consequence the most powerful type that is permitted to run between Banbury and Cheltenham. The engine now backing on to the train will run it over the remainder of the journey to Barry, having already brought to-day's northbound “Ports-to-Ports” express from Barry to Banbury. And we shall find that our new steed is well up to its task and will have no difficulty in making speed or maintaining time.

We leave Banbury at 3.37 p.m., and run 3½ miles along the Great Western North main line to our divergence to the right at King’s Sutton. For 1¾ miles the branch is double line, but after that we take to single-line working for 34½ miles to Andoversford. There are therefore frequent severe slowings for exchanging the single line tokens. As there are also long and severe grades, such as 7½ miles up at 1 in 100 from Bloxham to Rollright, a similar distance down as steep in parts as 1 in 80 to Kingham, and ups-and-downs steepening finally to 1 in 60, this is not exactly an “express” route. For the 44¾ miles from Banbury to Cheltenham South, including three “conditional” stops, the time allowed is 80 minutes, and it is fully needed. By contrast, the eight miles from Cheltenham to Gloucester are smartly run in 11 minutes, and we reach there at 5.10 p.m.

Now for the interesting note I was going to give you about those Midland coaches that accompanied us from Newcastle to York. They followed us out of York at 12.8 p.m., as far as Dearne Junction. There they passed on to the Midland main line and ran into the Midland Station at Sheffield, which they reached at 1.21 p.m., 21 minutes after we left Victoria Station. Since then they have travelled down through Derby and Birmingham, and now, if you please, between the Midland stations of Cheltenham and Gloucester, they run for six miles from Lansdown Junction over exactly the same metals as ourselves, and just five minutes behind us! This really is a rather remarkable fact.

From Gloucester onward we have to travel over the original main line to South Wales that the Great Western used from London before the Severn Tunnel had been bored. It is practically level and there is some good going, the time allowed between leaving Gloucester at 5.18 p.m. and reaching Newport at 6.24 p.m. being 66 minutes for the 44½ miles, including the stop at Chepstow. In the opposite direction the “Ports-to-Ports” express has only 59 minutes for the same run, the smartest time being 32 minutes for the 27½ miles from Chepstow to Gloucester.

There is much of interest to be seen along this stretch, as from Newnham onward we have the wide estuary of the Severn on our left for nearly 25 miles. Approaching Lydney we see the striking bridge that has been thrown across the Severn between there and Sharpness, carrying a single line that is the joint property of the G.W. and L.M.S. Railways. The only occasion when express trains are passed over this structure, which can carry but limited locomotive weights, is when the Severn Tunnel is closed at times on Sundays for repairs. Another interesting bridge, designed by Brunei, and of considerable size, carries us across the mouth of the River Wye, at Chepstow.

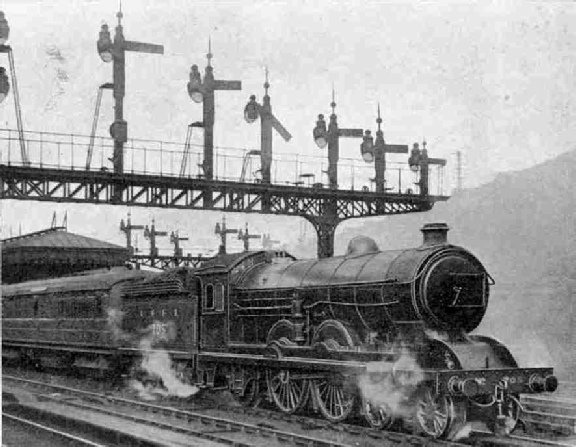

The “Ports-to-Ports” Express passing over Charwelton Water Troughs near Woodford, hauled by Great Central “Atlantic” No. 5360.

Hurrying on, we run over the Severn Tunnel - which is unseen, of course, but betrayed by the ventilating shafts coming up to the surface - and immediately afterward notice the deep cutting bringing the main line up on our right to join us at Severn Tunnel Junction. A little less than 10 miles farther on, heralded by extensive suburbs and the many chimneys that speak of industrial activity, we run into the city of Newport. A prominent object to the left of the line, before and after Newport, is the high transporter bridge over the mouth of the River Usk, which river we cross immediately before running into Newport Station.

The Great Western Railway have recently spent a great deal of money in modernising Newport Station, and the work is not yet complete. One of the alterations has been a considerable addition to the length of the main platforms, and the down platform, at which we are now stopping, is no less than 1,500 ft. in length. From here to Cardiff is but a short run of 11¾ miles, and takes 17 minutes. We see near both towns many hundreds of coal wagons, bearing witness to the busy neighbouring industry of the Welsh Valleys, which pour their product down to Newport and Cardiff for shipment at their extensive docks. The docks at Newport, Cardiff, Penarth, Barry, Port Talbot, Swansea and elsewhere in South Wales, together make the Great Western Railway the largest dock-owning company in the world.

Cardiff is reached at 6.47 p.m., and the only section now remaining is the short run of 9¼ miles to Barry. Leaving the big General Station at Cardiff at 6.55 p.m., and stopping only at Barry Docks, we come to rest in Barry at 7.20 p.m.

Since 9.30 this morning we have travelled 352 miles, and our average speed of nearly 36 miles an hour over this difficult cross-country route has, we shall agree, been quite a creditable performance. So now we must leave the “Ports-to-Ports” express to rest for the night, ready to begin its journey back to the North-East Coast ports at 9.5 a.m. to-morrow morning.

The “Ports-to-Ports” Express at Cardiff, with L.N.E.R. Stock and G.W.R. locomotive.

You can read more about the “3.20 Down Manchester”, “Cross Country Routes”, and “The North Country Continental” on this website.