Through the Alpine Barrier to the Heart of Italy

FAMOUS TRAINS - 10

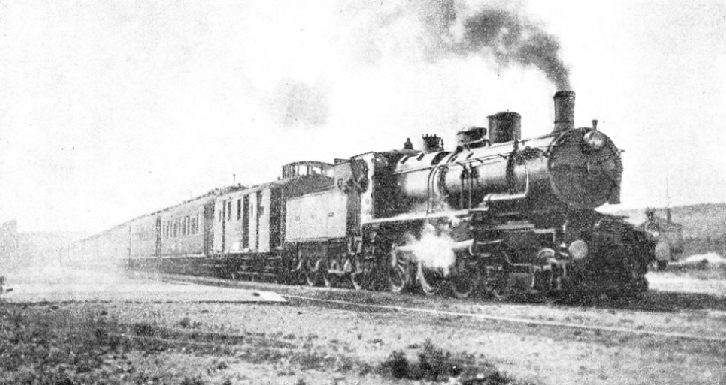

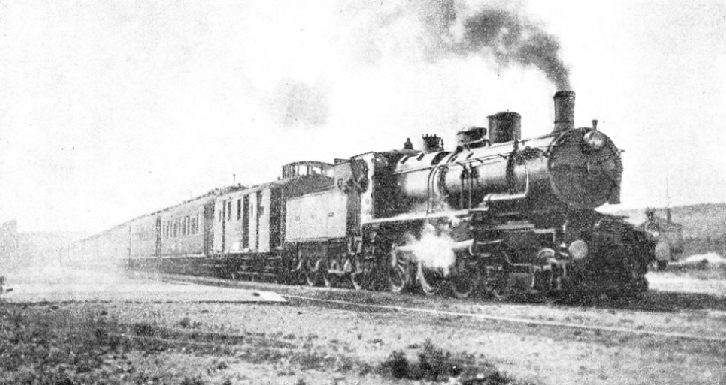

ON THE NORTHERN RAILWAY OF FRANCE through coaches for the “Rome Express” are run from Calais to the Gare du Nord at Paris. From that station the coaches are worked round on the Paris Ceinture Line to the Gare de Lyon, the PLM terminus, where the main portion of the “Rome Express” begins its journey. The picture shows a luxury train of earlier years passing over the Nord line.

The title of the “Rome Express” recalls to mind the old proverb: “All roads lead to Rome”. Two thousand years ago Rome was the centre of the world’s land transport system, for it was the capital city of the only people who knew how to build a really good road. To-day, even though the “Eternal City” is no longer a world transport centre, it is a goal for passengers from all parts of the continent of Europe.

It may be thought that traffic passing into Italy from the North is destined for Italy alone on every occasion, that country being a peninsula. This is not so, however. Travellers to the Levant often go by train to Venice, Trieste, or Brindisi, continuing their journey by sea. The “Rome Express”, however, is all-Italian in its destination. It is not such a veteran as its sister-train the “Orient Express”, for it did not begin regular running until November 15, 1897. At first the “Rome Express” ran only during the winter months, and then but once a week, the Italian summer climate not being agreeable to the majority of Northern Europeans, for whom the train was mainly operated. At the end of the last century, therefore, the rich man or woman who always wintered in Italy, after braving the accommodation offered by the London, Chatham and Dover Railway and the contemporary cross-Channel steamer, would find a truly gorgeous train awaiting him on the quay at Calais.

Those old International Sleeping Cars were rather too gorgeous. They annoyed the late Mr. Arnold Bennett so much that he said they were not half as spacious and comfortable as an ordinary first-class carriage running on an English main-line railway. Yet most people who travelled on this train were thrilled by their journey through France and Italy.

At the time of its inauguration, the “Rome Express” left Calais at 12.49 mid-day and arrived at Rome at 10.25 on the evening of the following day. In view of the general operating conditions of the period, especially in Italy, this was remarkably good running. The cars contained four berths in each compartment, and in this way were little superior to the original rolling-stock on the “Orient Express”. Gas lighting and steam heating were incorporated. The exterior of the old train was handsome enough, though some of the old-fashioned Continental locomotives which hauled it at that time were of rather alarming appearance. The four-berths compartments gave way to the double berth type in 1901, and single-berth compartments, generally similar to those on British trains, but convertible for day use, appeared in 1923.

During the war of 1914-18, although so-called “express” trains still connected Paris with Rome, the famous train was suspended. The Calais-Paris section of the route was close to the area of hostilities, while the long single-track sections across the Alps to Italy were congested with troop trains maintaining communication with the southern port of Taranto. On these through troop trains might occasionally be found rolling stock belonging to the former Midland and London and South-Western Railways of England.

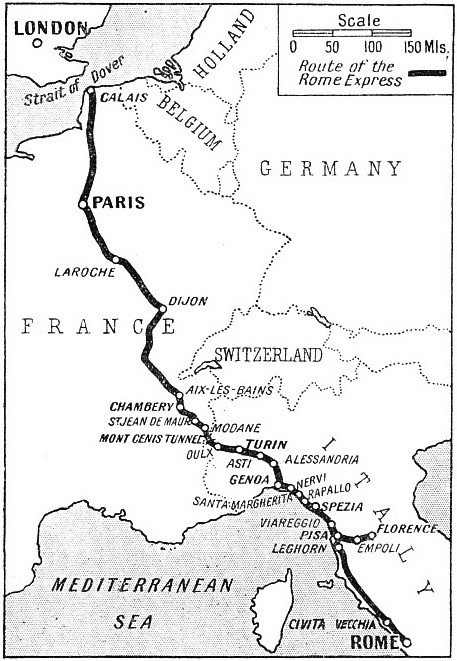

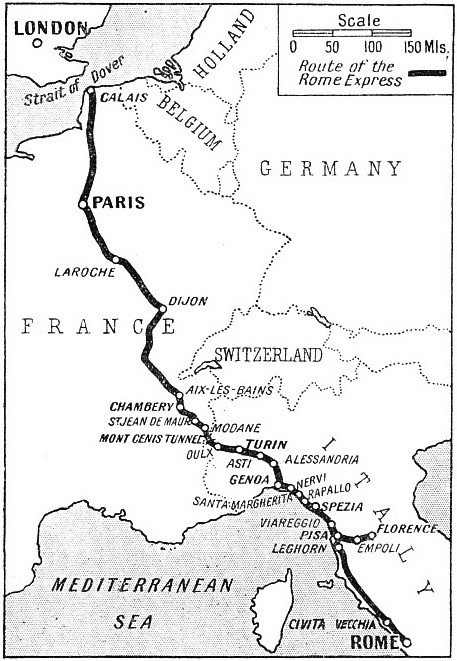

NINE HUNDRED MILES are covered between Paris and Rome by the “Rome Express” on the this route in under twenty-two hours. The train began regular service in 1897.

After the war the “Rome Express” began to make several ambitious extensions. It was one of the first of the great trans-European trains to recommence running. Though it took over thirty hours to cover the ground between Paris and Rome, which was considerably slower running than that set by the pre-war standard, it carried, in 1920, a through coach to Taranto, which in 1921 ran on to Brindisi. In the latter year, too, a car was run through to Naples. In 1924 through coaches from the Channel coast - at Boulogne this time - ran to Florence and Rome.

In 1930 even Palermo, in Sicily, was brought into the range of the through coaches from Boulogne on four days a week. At the present time, in the same way as the “Orient Express” and its even closer relation the “Berlin-Rome Express”, the “Rome Express” is notable also in another way. For a considerable part of its journey electricity is the motive power. That, however, will be mentioned more fully later on. To-day, also, the train is no longer as exclusive as it was, for it carries first-and second-class passengers.

Passengers from London leave Victoria at 11 am. The Southern Railway’s boat express is primarily part of the “Golden Arrow” service between London and Paris, described in the chapter beginning on page 232. The connecting boat from Dover arrives at Calais at 2.50 pm. As with the “Orient Express”, we shall perhaps see at Calais only two sleeping cars attached to an ordinary Northern Railway of France boat train, which follows the route of the “Golden Arrow” through Boulogne, Abbeville, and Amiens to the Gare du Nord in Paris. Thence the through sleeping cars are worked round the Paris Ceinture or “Belt” Railway to the PLM Terminus of the Gare de Lyon.

There is great romance in the Gare de Lyon. It is a gateway to the South, just as King’s Cross and the fine Central Station at Hamburg are gateways to the North, and as the West Station at Vienna, in spite of its name, is a gateway to the East. In his delightful novel of that name, the late William J. Locke sent his Beloved Vagabond out on to the Pont Neuf in Paris, to ask the statue of Henry IV whither he should go. The statue, he said, smiled down at him and pointed to the Gare de Lyon. The Beloved Vagabond went into the Gare de Lyon, and found a train just starting for Italy. “So,” he said, “I went to Italy.”

But that charming character probably went third class, and at the moment we are concerned with the “Rome Express”, which could not have catered for him. At the Gare de Lyon the rest of the train, consisting of long sleeping cars, a dining car, and two luggage vans, one containing a bathroom, will be found waiting at one of the departure platforms. All the cars are beautifully fitted and most comfortable.

As we rumble out to the south at twenty minutes past eight, an excellent French dinner is announced from the restaurant car. A night train getting into its stride is one of the best places in the world in which to enjoy a good dinner, and by the time the meal is over the “Rome Express” is well away from the neighbourhood of the French capital, hurrying through the darkness of Central France. There is nothing to do but read, relax and digest the meal until the berths are made up for the night. Although the PLM has recently introduced some fast timings on its lines, the “Rome Express” is not particularly speedy. It progresses southwards through France at a long, easy swing, and reaches Dijon, 195 miles, twenty-two minutes after midnight, with one stop, at Laroche. From Paris to Laroche, ninety-six miles away, a “Pacific” locomotive is used. Over the next stage, to Dijon, in view of the long climb to Blaisy-Bas Summit, a powerful 4-8-2 will probably be substituted. Haulage between Dijon and Chambery may be entrusted to a 4-8-2, 4-6-2, or 2-8-2 locomotive.

LEAVING PARIS. The “Rome Express”, headed by a “Pacific” locomotive. The train departs from the Gare de Lyon at

8.20 pm. The first stop is at Laroche, ninety-six miles distant.

All is quiet on the cars as the train rolls out of Dijon, and bears away from the main line to Marseilles in a curve to east-wards. It is still dark when, at 3.49 am, the train draws up at its next stopping-place, Aix-les-Bains. If there is a good moon, those who may be awake can see that the line has reached the foothills of the Alps, high mountains rising on either side. Aix-les-Bains is a pleasant spot, but it is not to be recommended as a holiday resort for the young and energetically-minded. It is too full of recuperating politicians and elderly persons undergoing the cure. There are plenty of mountain resorts less sacred to companions of this nature, and one of these is Chambery, 175 miles from Dijon, where the train stops at 4.5 am.

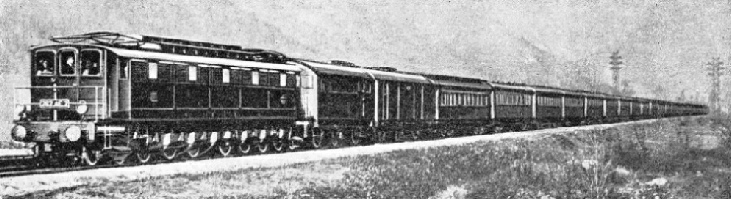

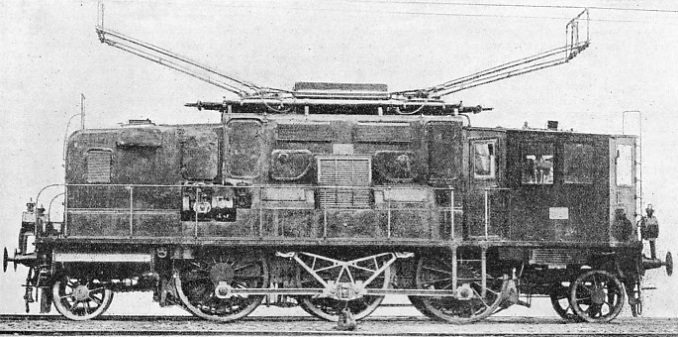

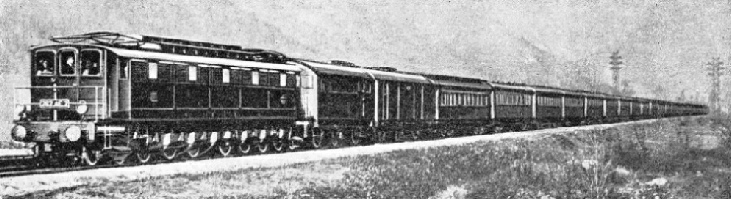

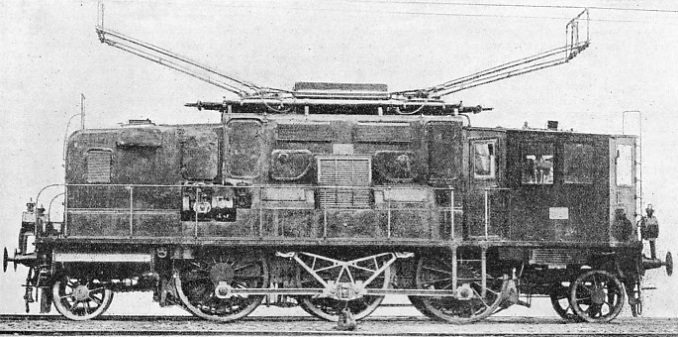

At Chambery a change-over to electric traction is made, and we shall be far down in Italy before a familiar puffing comes once more from the head of the train. The electric locomotives of the PLM are peculiar. They collect current from a third rail at the side of the running rails while in open country, but in the stations and sidings overhead wires are provided, the loco-motives being fitted with pantograph bows as well as collector shoes. This is to render the movements of shunters and station porters in the yards and sidings less dangerous. In Italy there is a different system of electrification, and it is possible to study the two systems side by side in the station of Modane, on the Italian frontier.

A TWENTY-WHEELED ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE hauls the “Rome Express” on the PLM section between Chambery and Modane. In open country the electric locomotives of the PLM take current from a third rail, while in stations and sidings current is collected from overhead wires.

From Chambery onwards to Modane, through St. Jean de Maurienne, the only intermediate stop, the train passes through magnificent mountain scenery. If the passenger is travelling at the right time of year, and if the weather is fortunate, he will be treated to a sunrise effect not easily forgotten. Most of us, however, are not fond of early rising, and many sunrises come and go without being appreciated. Not infrequently it is a night train, roaring up through the morning mists, that gives the best view of the most beautiful of all natural phenomena. A fine effect, which has been lost with the coming of electric traction over the mountain section, was that made by the columns of snowy-white vapour which used to rise high into the morning air from the locomotives at either end of the train as it climbed steadily up to the Mont Cenis Tunnel. The smuts and coal-dust from those labouring engines used to be rather formidable, and settled in thick layers on the carriage window-sills. But there was nothing to beat the grandeur of the effect as the engines crept up the valley with their high smoke-plumes above them.

Modane, where we leave the PLM, is an interesting place. It might be in either France or Italy, and its name might belong to either language. It is in France, in the extreme south of the department of Savoy, through whose mountains the “Rome Express” has been passing since it left the country preceding Aix-les-Bains. Modane is a single straggling Alpine township shut in, apparently on all sides, by high mountains. The “Rome Express” reaches it at 5.45 am, roughly five hours and twenty minutes after leaving Dijon, 235 miles away. This is remarkably good running when we consider the climbing which has been done.

At Modane most trains undergo official examination by the Italian Customs officials and frontier police, but in the present instance this is carried out on the train itself. Soon we shall be familiar with the black-shirted military railway police, who are to be found on the trains, stations, and tracks all over Italy.

The train waits at Modane for half an hour, but as Italy sets her clocks by Central European time, our watches point to 7.15 (if we have put them on properly) when the “Rome Express” glides out to cross the frontier behind an electric locomotive belonging to the Italian State Railways. The Italian electric locomotives work on the three-phase system, consequently double collector bows are mounted on the cab roofs, and there are two conductor wires overhead instead of one for each track. Before the great Mont Cenis Tunnel was opened in 1871, a 3 ft 7 in gauge line, constructed on the principle invented by Mr. J. B. Fell, carried passengers, goods, and mails right over the Mont Cenis Pass, topping a summit nearly 7,000 feet above sea level. This was long before the “Rome Express” started running; but it is worth recalling. (The Fell system is described in the chapter, “Rack Rail Locomotives”). On the Mont Cenis route, of course, the Fell line ceased to operate after the construction of the tunnel, but it had three years of useful life.

THE “ROME EXPRESS” is hauled over the line between Modane and Leghorn, a distance of 274 miles, by an Italian electric locomotive of this type. The locomotive is put on at Modane and hauls the express through the Mont Cenis Tunnel.

After leaving Modane, and before entering the Mont Cenis Tunnel, the line rounds a complete horse-shoe curve, rising all the way. The Mont Cenis is the oldest of the great Alpine tunnels, and we wonder at the perseverance of its builders all the more when we realize that the whole of its length of 8 miles 832 yards was bored without the aid of pneumatic rock-drills or any of the modem appliances which are now considered essential to tunnel building. It is feared that Mark Twain, when he went to Turin, was not properly reverent, for he said that he travelled by a railway profusely decorated with tunnels, and that as he had omitted to bring a lantern along with him, he missed all the scenery.

The “Rome Express” tops its Alpine summit-level as it passes through the Mont Cenis Tunnel. As we feel the speed gradually increase, we realize that we are beginning to run down into Italy. At the Italian end of the tunnel the train passes through a gallery in the face of the mountain before finally emerging into the open. Looking back, we obtain an unforgettable view of the great Alpine mountain mass, under which the train has passed, towering into the sky. At most times of the year it is thickly cloaked with snow. Mont Cenis Pass is 6,860 feet high, the summit being in Italy. It is, however, somewhat east of the wall of rock under which the railway finds its way for nearly eight and a half miles.

At first sight the country seems generally similar to that which we left behind at Modane, but even after a few minutes we begin to find differences. The whole feeling of the air is different on the southern side of the Alps. There is a different smell about; there are subtly different shades in the colouring. A strange little mountain town which is passed on the left side recalls the general idea of a town in Corsica. It is wild, romantic, and primitive. French mountain towns seem to have an air of trying to be respectable under difficulties. There is none of that false “respectability” in Italy.

Changes are noticeable, too, in the railway equipment. Instead of the characteristic “chess-board” signals of the French railways, we find strangely familiar square-cut red semaphores, with the usual white stripe across. Many of the Italian carriages, too, which we may see on northbound trains passing us, forcibly recall British practice with their side doors, curved sides and semi-elliptical roofs. The mainline electric traction on the three-phase system, however, has nothing familiar about it; in fact, Italy is one of the few countries to adopt this system extensively. The great barn-like, cream-washed station houses, also, are strange to British eyes, though similar houses are seen in Germany.

The first stop made by the “Rome Express” in Italian territory is at Oulx-Clavieres-Sestrieires, only nineteen miles from Modane. The station after, at which the train does not stop, has an even less Italian-sounding name, Sal-bertrand. These are reminders of the Nordic origin of many of the people in Piedmont and Lombardy. In the same way, the traveller finds Welsh-sounding Celtic names in the heart of German-speaking Switzerland.

The train continues to slip down through a relatively narrow belt of Alpine foothills into the great plain of North Italy, and by 9.15 am we are at Turin, fifty-eight miles from Modane.

Turin has a fine station, and the whole place is an interesting example of nineteenth century town-planning. It is here that the train is reversed; the tail becomes the head, and it goes out again behind another big electric engine. As far as Alessandria, the line still runs through the fiat Northern Plain, past picturesque farm buildings of the traditional Italian type, with great white oxen ploughing in the fields and drawing carts along the country roads beside the line.

Having left Turin at 9.25, the “Rome Express” calls at Asti at 10.8, and reaches Alessandria, 115 miles from Modane, a little under half an hour later. It will be noticed that there is, on the whole, less long-distance non-stop running in Italy than there was in France. But the train keeps good time, and there is smart running between the stations.

After Alessandria there is an end to the flat plains, for the train turns southwards and begins to climb into the Ligurian Apennines. At Ronco, 1,070 feet up and twenty-nine miles from Alessandria, we are practically on the back of the watershed, and the train soon runs down into Genoa past sunny south-facing hill-sides, arriving at the great and ancient seaport at 11.50. Genoa is 161 miles from Modane.

The station at Genoa always seems to be a place of many tongues. This is natural, for not only does it serve a great sea-port, but it is also a centre for international trains from many parts of the Continent. Coaches belonging to the Swiss Federal, German State, and Netherlands Railways are all seen in one train, bringing people down from Central Europe to the Riviera. Trains come in, too, from the Danubian countries, and even through coaches from the Balkans are seen.

Along the Gulf of Genoa

The station itself is bright and clean, but somehow rather cramped for space, and the “Rome Express”, were it worked by a steam engine, might give a sigh of relief as it slips out and continues its run along the coast. It is here that the electric locomotive proves itself to be a great aid to comfort, for the whole stretch down past Rapallo and Spezia contains one long succession of tunnels through projecting cliffs.

The intervening glimpses of Italian coast scenery, however, are charming, especially in the spring, when the pink Juias-trees are out and the oranges are already taking a good colour. Rapallo is beautiful, and even Spezia manages to disguise her undeniably plain face behind masses of flowers and sub- tropical trees. Luncheon and the incessant tunnels fail to distract attention from these lovely snatches of scenery. After calling at Nervi, Santa Margherita, Rapallo, and Spezia, the train turns inland at Viareggio to historic Pisa. At Pisa the famous Leaning Tower, Cathedral, and Baptistery are clearly seen on the left side of the train as it enters the city.

From Pisa, the Florence cars are taken on eastwards via Empoli, the junction for Siena, arriving at Florence at 4.10 pm. In the meantime, however, the main part of the “Rome Express”, soon to be headed by a 2-6-2 steam locomotive, has hurried away down the coast.

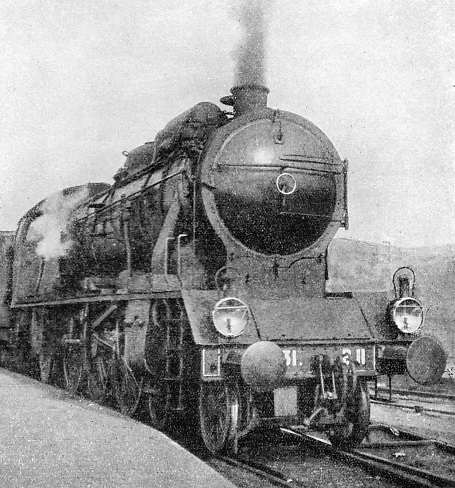

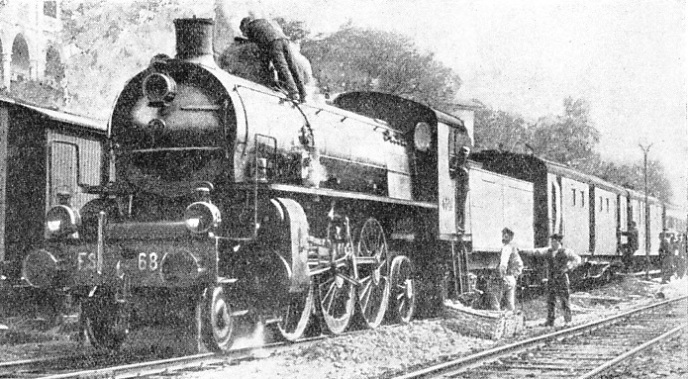

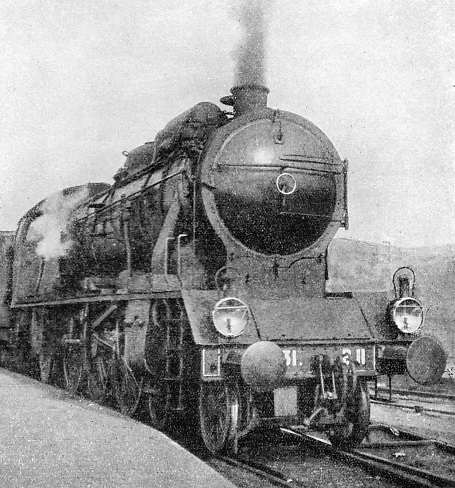

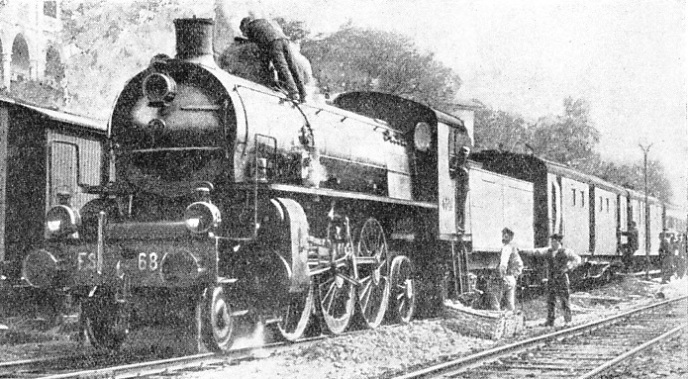

OVER STEAM-OPERATED LINES in Italy 2-6-2 locomotives of the type illustrated are employed extensively for fast passenger trains, including the “Rome Express”, on the 197-miles stretch between Leghorn and Rome. The man on the top of the engine in the illustration is inspecting the contents of the sand-box.

Continuing south we reach Leghorn at one minute past three in the afternoon. It is here, 274 miles from Modane, that the change over to steam traction is made. We have covered, from Chambery, an all-electric stretch of railway 334 miles long. The Italians, in the same way as the Swedes, have made railway electrification a matter of national policy, and they are carrying it out very ably indeed.

Notable external features of our new steed are the conical front, the large combined dome and sandbox, and above all the Fascist emblem of axe and faggots set in front of the chimney. The Fascist emblem is seen on all locomotives of the Italian State Railways.

Beyond Leghorn the sea-coast is less impressive than it was on the Italian Riviera, but the tideless Mediterranean can be beautiful enough anywhere under good conditions.

Although steam trains are generally slower in Italy than electric trains, it is on this last lap that the “Rome Express” begins to sprint again, for the well-patronized resorts between Genoa and Pisa have been left behind, and the train proceeds to run from Leghorn to Rome without a single booked intermediate stop, the distance being 197 miles. The Italian railways have no track water troughs, however, so we do not really have an unbroken nonstop run, a halt being made at Grosseto for water. Curiously enough, too, the following ordinary express train - the 9.5 am from Modane, does rather more non-stop running than the “Rome Express”, for it has no booked stops between Turin and Genoa, or again between Genoa and Pisa.

On the last stretch along the coast the “Rome Express” recalls ancient history when it passes Tarquinia, which takes its name from the line of legendary kings who ruled over ancient Rome before she became a republic and expelled Tarquin II in 509 BC. After Civita Vecchia, too, we pass the ancient port of Rome before striking inland across the Campagna.

At a distance of 471 miles from Modane and at 7.5 pm, the “Rome Express” rolls into the great terminal station of the city of the Caesars.

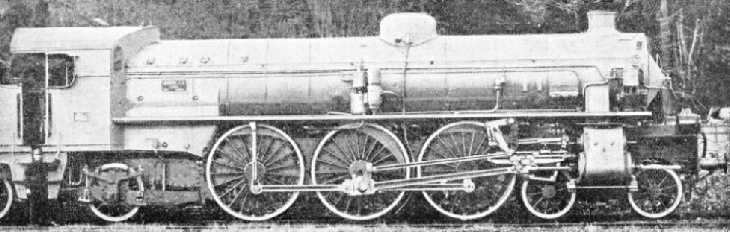

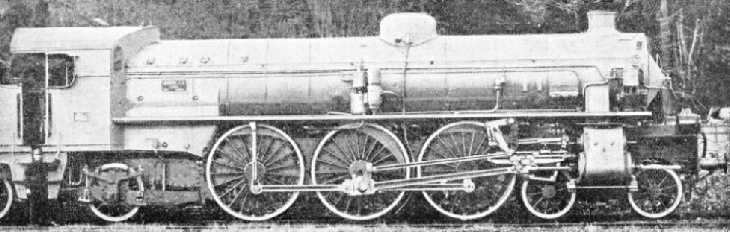

AN ITALIAN “PACIFIC” locomotive built for express services in 1932. The heating surface is 2,368 sq ft, and working pressure 227½ lb. There are four cylinders - simple -17¾ by 26¾ in. The coupled wheels measure 6 ft 8 in, and the weight of the engine in working order, without tender, is 89 tons. The reversion to simple expansion recalls modern British practice.

Here, for most of us, is the end of the journey. The train goes forward, however, and, after fast running across the grey-green plains of the Campagna, once more behind an electric locomotive, it reaches Naples three hours later. For those who are travelling through to Sicily, there is another night journey in store, and the berths are put up in the through car. After leaving Rome, this Palermo car is taken southwards through the Campagna, then through Calabria - the “toe” of Italy, arriving at Reggio on the following morning. Thence to Messina it is taken across the intervening straits on one of the fine modern train ferries, to run along the north coast of Sicily.

Apart from the passenger traffic handled by the Italian State Railways’ ferries between Sicily and the mainland, there is also a considerable fruit traffic. Much of this Sicilian produce is conveyed in special containers for cities in Northern and Central Europe.

Sicily is different from Italy, just as Scotland is different from England. The inhabitants have a strong Greek strain in their blood, so that the racial difference draws a double parallel. To the southwards, as the train steams along past Barcelona and Patti, there is a superb view of the perfect cloud-tipped outline of Mount Etna, while on the other side the Lipari Islands - perhaps even Stromboli is visible - stand out as jewels in the sea. Finally, at 9.15 in the morning of the third day after leaving London, this farthest South connexion of the “Rome Express’’ is brought into the brilliantly sunny city of Palermo.

The Sicilian lines are part of the Italian State Railways, whose standard rolling-stock is to be found on them. Many years ago, however, some American-built Pullman cars found their way to Italy, and the Italian railways are said also to have bought some Pullmans, second-hand, from the old Midland Railway in England, when that company decided to build and run its own sleeping and dining cars. Old Pullmans were still to be seen on Sicilian express trains quite recently. One or two old express engines were sold to Italy, too, by the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, and rumour has it that one, either “Connaught” or “Edinburgh”, was at work in Sicily at the time of the Messina earthquake, in which it was destroyed. These, however, are matters quite unconnected with our old-established, but essentially modern friend, the “Rome Express”.

An other interesting fact that the traveller should remember while on the “Rome Express” is the change of time from Greenwich to Central European time, and vice-versa, referred to earlier in this chapter. This occurs at Modane both on the outward and on the return journey, and has the effect of making the journey time seem about an hour less from Rome to Paris than from Paris to Rome. After due adjustment has been made, however, it will be found that the outward journey is quicker.

other interesting fact that the traveller should remember while on the “Rome Express” is the change of time from Greenwich to Central European time, and vice-versa, referred to earlier in this chapter. This occurs at Modane both on the outward and on the return journey, and has the effect of making the journey time seem about an hour less from Rome to Paris than from Paris to Rome. After due adjustment has been made, however, it will be found that the outward journey is quicker.

ALONG THE ITALIAN COAST, between the stations of Genoa and Spezia, the “Rome Express” has to pass through a succession of tunnels bored through projecting cliffs. This illustration shows Nervi station, seven miles east of Genoa.

You can read more on “Italy’s Chilled Freight”, “Modern Construction in Italy” and “The Rome Naples Direttissima” on this website.

other interesting fact that the traveller should remember while on the “Rome Express” is the change of time from Greenwich to Central European time, and vice-

other interesting fact that the traveller should remember while on the “Rome Express” is the change of time from Greenwich to Central European time, and vice-