© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

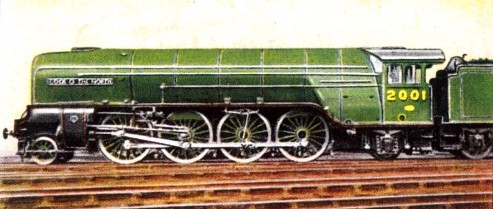

A Test Run on “Cock o’ the North”

Hill Climbing Feats of New Locomotive

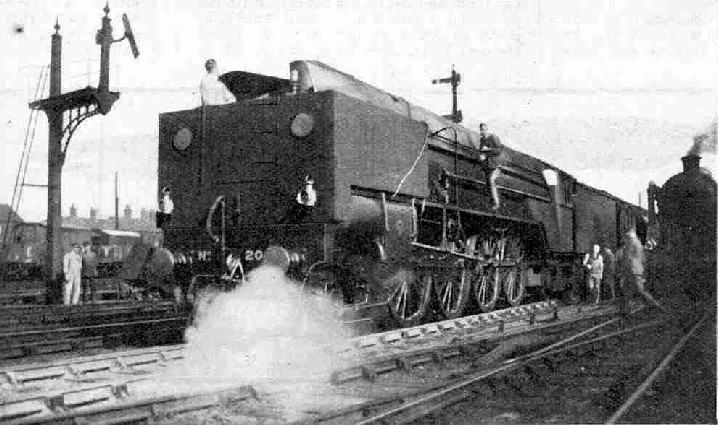

LNER Locomotive No. 2001, “Cock o’ the North”, at Peterborough during a trial run. The engine is fitted with an indicator shelter and a dynamometer car is coupled to the tender.

READERS were promised an account of a footplate trip on “Cock o’ the North”, the magnificent 2-

A preliminary test was made on Tuesday, 19th June 1934, when the engine hauled a specially made up train with the enormous weight of 650 tons from London to Grantham and back with great success. During the first week in July, a series of “full dress’’ trials were carried out. Each day the engine worked the 11.04 a.m. up Yorkshire Luncheon Car express from Doncaster to London and returned on the very heavy 4 p.m. train, which carries in addition a portion for Grimsby and Cleethorpes.

On these journeys every single feature of the engine’s working was under the closest observation. Steam indicators were fitted to the cylinders for measuring the horse power developed. A shelter was erected round the smoke-

Immediately behind the tender, in front of the ordinary passenger coaches, was coupled the dynamometer car. This marvellous vehicle is a completely equipped engineering laboratory on wheels. Under the floor is a strong spring, one end of which, called the “live” end, is attached to the tender coupling. Acting just like a great spring balance, it measures the pull exerted by the engine To start a 650-

Many other quantities are measured, among them the amount of coal, oil and water used and the temperature of the steam at various points Even the exhaust gases in the smoke-

During the interesting test week I travelled with “Cock o’ the North” on a run with the 4 p.m. express from King’s Cross, and witnessed a magnificent performance the load consisted of 16 bogie coaches and the dynamometer car, weighing 548 tons empty and 585 tons with passengers and luggage. No attempt was made to break records the object of the test was to work the train to schedule time in the most economical manner.

We made a fine start. From King’s Cross the line rises steeply at 1 in 105 out to Holloway, yet “Cock o’ the North” passed the top of the rise, 1¾ miles out in 5¼ minutes. By Finsbury Park, still climbing, the speed had risen to nearly 40 mph and the short slightly downhill “breathing space” to Wood Green quickly brought speed up to 54 mph before we tackled the mile climb at 1 in 200 to Potters Bar. At Holloway the cut off had been brought down to about 25 per cent , and through Wood Green it was only about 15 per cent. In fact, it was only when we were halfway up the Potters Bar bank that cut-

Thus we passed Potters Bar, 12¾ miles, in 20¼ minutes, and here the cut-

Still working on 10 per cent cut-

The engine was now blowing off steam furiously, showing full boiler pressure, and this despite very easy firing. For Stukeley Bank, nearly four miles at 1 in 200, cut-

Now came a most extraordinary feat. When we reached the level at the foot of the bank, steam was shut off altogether, as we were well on time, and the valves were put into mid-

A long slowing to 30 mph for permanent way repairs was in force through Yaxley, but we came into Peterborough, 76½ miles from King’s Cross, in 85 minutes, the net time being about 82 minutes.

Perhaps the finest feat yet achieved by the engine is a “flying” ascent of Stoke bank, the 10 miles of this incline, with a gradient of 1 in 200 to 1 in 178, being climbed at a minimum speed of 56½ mph with 650 tons! The engine’s remarkable hill-

“Cock o’ the North” is the first eight-

You can read more on “Cock o’ the North”, “How Engines are Tested” and “Testing a Locomotive” on this website.

Visit the Cock o’ the North website.