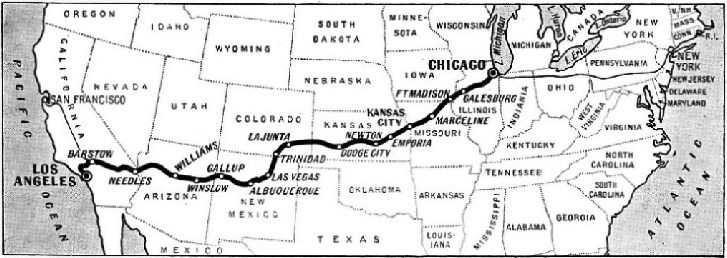

A Journey of 2,228 Miles Across the United States

FAMOUS TRAINS - 5

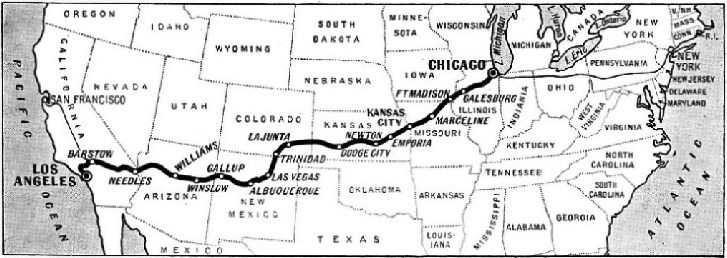

FROM LAKE MICHIGAN TO THE PACIFIC, the route of the great express connects two of America’s greatest cities.

A FEW minutes before noon on a certain day many years ago a man wearing a cheap serge suit, cowboy hat and fiery red tie walked into the office of the Santa Fé lines in Los Angeles and demanded to see the assistant traffic manager.

“I want to take a train over your road to Chicago”, the stranger said, “and I want you to do it in forty-six hours; that is nearly twelve hours faster than the eastbound run has ever been made. The fact is - I’m buying speed, and I don’t care what I pay for it”.

He began to shed a number of thousand-dollar bills, the assistant traffic manager made a few pencilled calculations, and at the conclusion of the conference five thousand five hundred dollars had exchanged hands and the Santa Fé line had agreed to carry their speed-eager passenger from Los Angeles to Chicago in forty-six hours, provided steam and steel should hold together.

The name of the unusual visitor was Walter Scott, a miner of wealth combined with sporting tendencies, and although he had done the trip over thirty times before, he felt that the day had come when the railway should be put to a really gruelling speed test. Besides, Mr. Scott had the money and he was entitled to use it as he wished, so long as the railway company considered that the feat which he demanded was within the bounds of possibility.

So, at one o’clock in the afternoon of Sunday, July 9, 1905, Mr. Scott’s special train pulled out of La Grande Station of the Santa Fé system at Los Angeles, engine No. 442 hauling baggage-car, dining-car, a standard Pullman car and, of course, Mr. Scott. The weight of the train came to 170 tons. At 11.54 am on July 11, Mr. Scott’s “special” came to a stop in the Dearborn Street Station, Chicago, having made the run of 2,228 miles in 44 hours 54 minutes. This was the train that is known to history as the “Death Valley Coyote” or the “Scott Special”. During parts of the journey, which was not without misfortunes, the enthusiastic passenger helped with the stoking, and it is claimed that the highest speed attained during the trip was over 100 miles an hour, between Fort Madison and Galesburg.

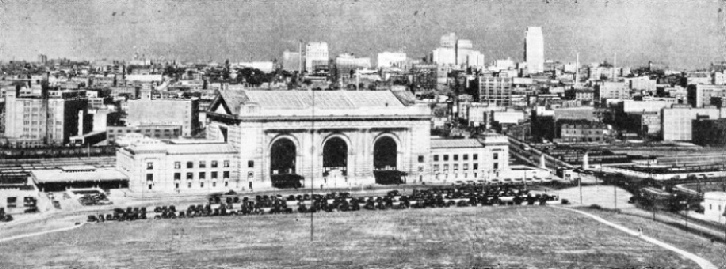

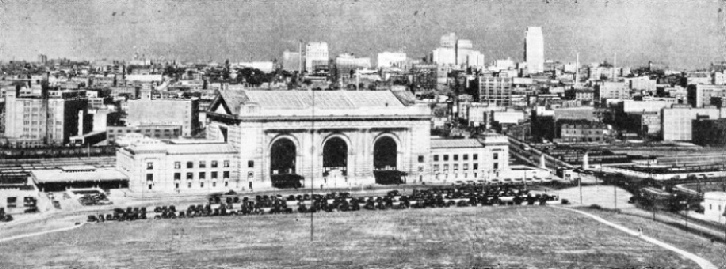

KANSAS CITY, with if typical American skyline, is reached at 9.35 pm on the first day. The “Chief” leaves again at 9.50 pm.

The average speed, including delays, was 50.4 miles an hour, an extraordinary figure considering the distance and character of the route, which runs through extraordinarily varied country and at times climbs to very high altitudes. The engines used were of the “Pacific”, “Prairie” and other types, as well as the “Atlantic” type of balanced compound engine. Changing engines at divisional points was cut to a fine art, a novel plan being adopted to save time. The fresh engine was backed on to the main line just ahead of a crossover before which the special train would stop. The old locomotive was cut out and was run over to a siding, the new one being coupled on without delay. The fastest change-over took eighty seconds.

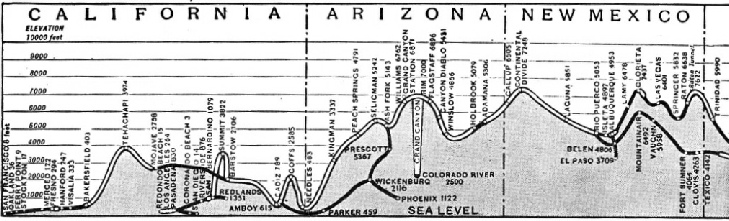

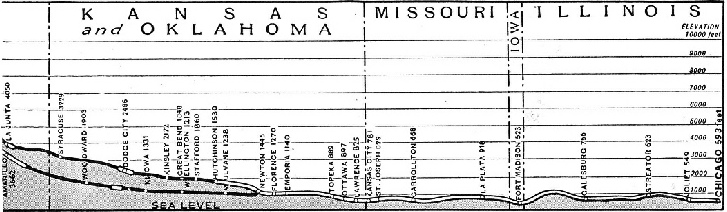

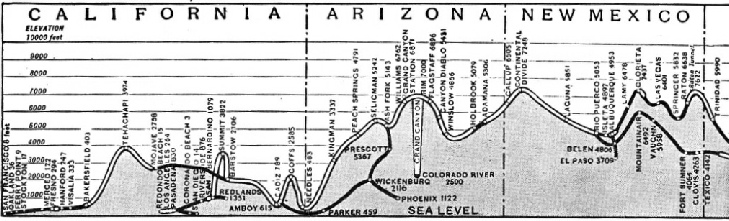

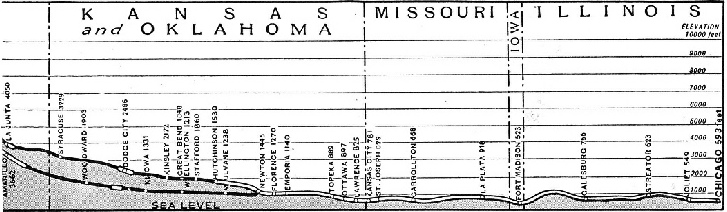

TRANS-CONTINENTAL GRADIENTS are shown at a glance by this contour diagram. Starting from Chicago (below right) the line is comparatively level through Illinois, Iowa, and Missouri, after which it climbs (by the higher route) through the mountains. An elevation of 7,622 ft is reached at the Raton Tunnel in New Mexico. The amazing Grand Canyon, in Arizona, can clearly be seen on this diagram (above). From Grand canyon Station there is a spectacular drop of 6,388 ft down to Needles. The double lines represent double track and the black, single track.

Scott’s run became nation wide in its interest. It was front-page news, although it was later suggested that the journey was made merely as a publicity scheme and that Scott had received a reward rather than having paid a large sum of money for a specially chartered train. The journey was, however, a genuine one of good faith. The fame that descended on Mr. Scott was merely the aftermath which he had not anticipated.

Air-Conditioning

Through the speed anxiety of Mr. Walter Scott it became clear to the Santa Fé system that there were hardly any limits to improvements in running time, and even to-day this railway company will undertake specially chartered journeys if they are humanly possible. The real value of the journey of the “Death Valley Coyote”, or the “Scott Special”, lay in the fact that it emphasized more than ever the necessity of cutting down the time-distance between the Pacific Coast and Chicago. The Santa Fé system has been making continual improvements on its line, commensurate with the preservation of safety and comfort. Scott was, in a way, a pioneer of the present fastest train to run over the Santa Fé line between Chicago and San Diego, namely, the celebrated “Chief”. which has in recent years become more famous, since it is used so much by film people travelling to and from Los Angeles (for Hollywood).

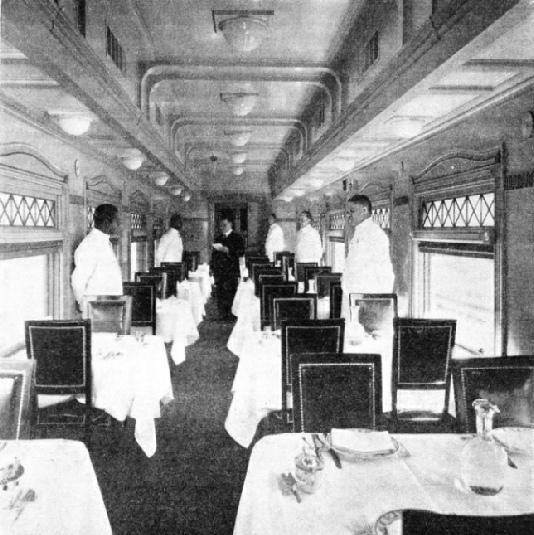

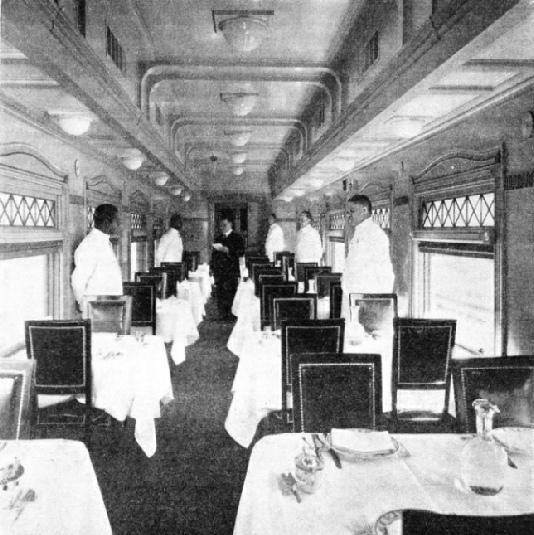

THE FIRST AIR-CONDITIONED DINING-CAR in the West was that of the Santa Fé “Chief”. This picture shows one of the latest cars on this famous train.

There are at present five daily trains from Chicago to California, but the speediest is the “Chief”. It leaves Dearborn Station at 11 am, arriving at San Diego at 9.30 pm, two days later. There is an additional charge of a few dollars as an “extra fare” demanded for the train's special privileges. The “Chief” is frankly intended for those people who want the best. It is designed for men who demand the extra roaming space provided by the large club cars, and for women who love daintiness and immaculate surroundings.

Let us make a tour through this wonderful long-distance special. We will go into the club car first, for here we find all the comforts to which we are accustomed in our own towns. It is air-conditioned, and no matter what temperature may reign outside we are assured that the climate within will be to our liking. In the summer when the heat rises to 103 and 104 Fahrenheit outside we know that until we leave the train we shall not notice the temperature nor feel the blazing sun that beats down with such intensity, for example, during the journey over the Mojave desert.

Expert barbering is also obtainable, and there is the luxury of a shower bath for men as well as women; and we shall find that the shower is in constant demand during the tropical months in western America. Furthermore, the first air-cooled diner ever used in the West was installed on the “Chief” - a desirable innovation for summer-time travellers. Fine table linen, gleaming silver, harmonious decoration and immaculate daintiness everywhere serve to whet the appetite for the feast prepared under the skilled auspices of Fred Harvey, who is notable for the founding of an extraordinarily interesting chain of hotels in the United States.

Fred Harvey’s hotels are indeed remarkable, for they serve so many stations and are essentially a part of railway travel in America. The hotel at Albuquerque, on the Chicago-Los Angeles route, is a particularly fine example of hotel service; and here the traveller may descend to witness the haunts and customs of the Red Indian. The “Chief” stops here for awhile, and during the less-temperate seasons it is an experience to dismount from the air-cooled cars into the flaming heat and characteristic atmosphere of Albuquerque. Midway in the train and next to the diner is the special ten-section lounge car, with its luxurious settees and chairs and its tables with reading lamps. It is a recreation rendezvous, and since long-distance train travellers are marooned from other contacts during their journeys, it forms a pleasing meeting-place for friendships so often made on long-distance trains of this nature.

Passing through the sleeping-cars you notice that sleeping sections, drawing-rooms and compartments are so well contrived that they may be booked by the suite; indeed, the “Chief” is little less than a travelling hotel, so well is it designed and organized. The formation of suites is flexible, to accommodate family parties of mothers and fathers and children, with or without a personal maid, and various-sized family parties. This variability is achieved by the grouping in one car of six compartments and three drawing-rooms; in another, seven drawing-rooms; in still another, three compartments and two drawing-rooms, and so on.

At the rear of the train is the observation super-parlour car. Its settees and chairs promise ease and relaxation. It suggests a luxury comparable with that of a first-class hotel in any part of the world. In this part of the train there is also a lounge reserved for the use of women passengers, and a shower-bath for women and children only. A maid travels with the train to attend to the needs of the feminine travellers, a negro maid - as is the custom there - all shiny and clean, and ever ready to respond to the demands for service.

The Santa Fé “Chief” traverses the heart of romantic America. If you have once travelled on it you will inevitably want to repeat the experience, for the route taps the most remarkable scenery, including fertile farming sections, areas rich in mineral wealth, the arid wastes of the Mojave desert, the extraordinary district of Death Valley - and many other geographical features.

SUNNY CALIFORNIA is reached two days after the start from Chicago. This picture shows the Santa Fé station at San Bernardino, where the “Chief” has only sixty miles to go to Los Angeles, having travelled 2,168 miles from Chicago.

The train, too, is under one management all the way, and this makes for smoothness of running and general economy.

If you “stop off” at Albuquerque it is likely that you will make detours to see the Indian country; but you may pick up the “Chief” on any following day.

One of the attractive features of the Santa Fé line over which the “Chief” runs regularly every day is the variation in altitude covered by the line. Just before Raton, on the westward journey, the Raton Tunnel stands at 7,622 ft above sea level, and much of the elevation of the track is above the 5,000 ft level.

You may leave Chicago at 11 am in the morning and you will arrive in Los Angeles (which being translated means the City of the Angels) on the third day out at 5 pm. If you are going on to San Diego you will arrive in that city four and a half hours later. It is fitting that the railway world should salute the “Chief”.

DOUBLE-HEADED. Two locomotives are required to haul the “Chief” through country of this nature, where the altitude is 2,500 ft above sea level. This striking picture was taken in the Cajon Pass district, near San Bernardino, California.

You can read more on “The American Comet”, “The Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe Railway”,

“North American Railroads” and “Speed Trains of North America” on this website.