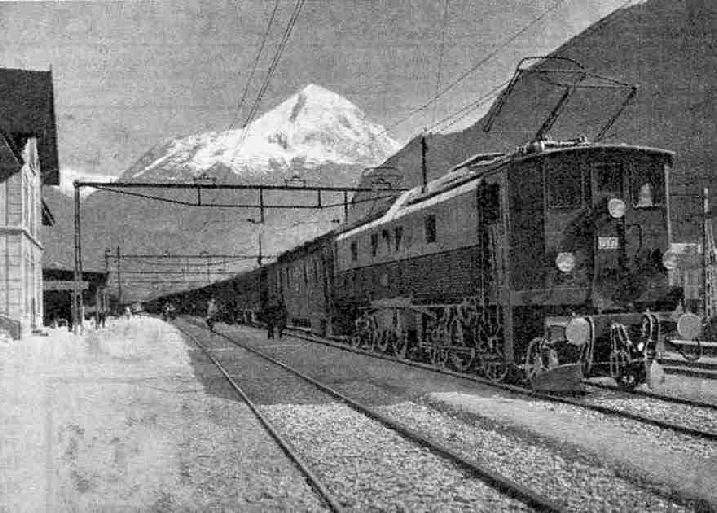

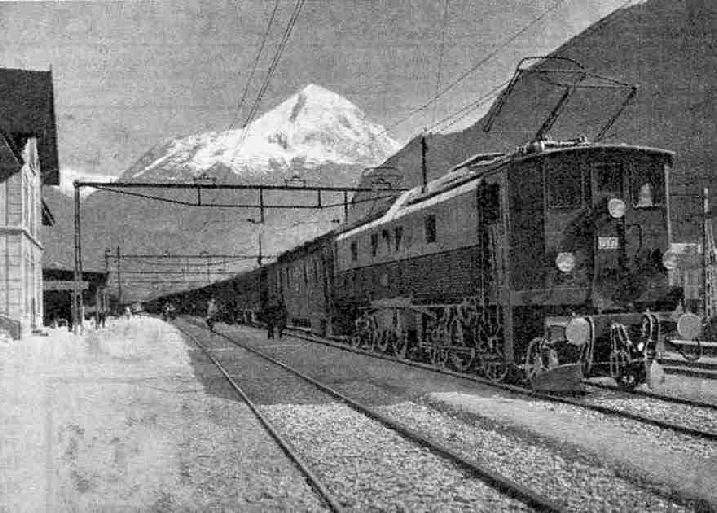

A Famous Train of the Swiss Federal Railways

FAMOUS TRAINS - 29

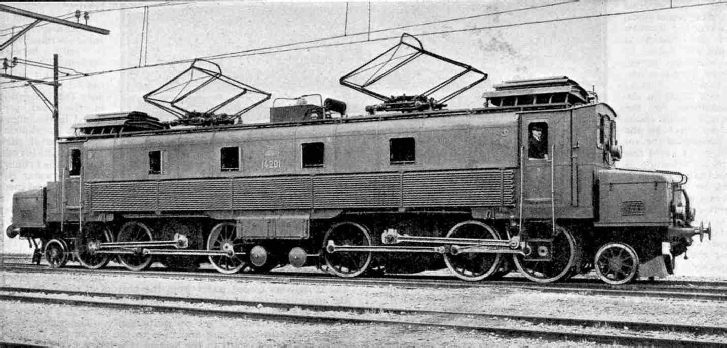

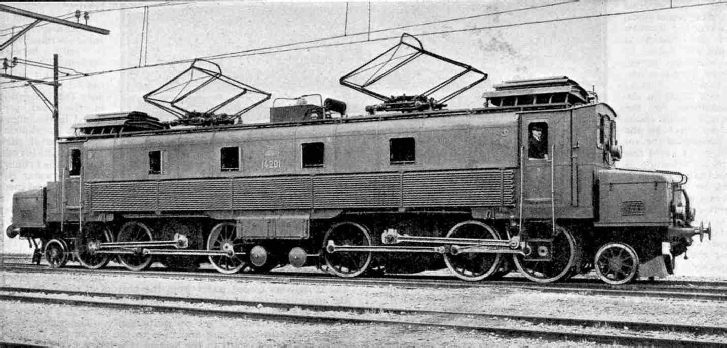

An Electric Locomotive of the Swiss Federal Railways.

THERE is a special purpose in the transfer of our attention from the railways of Great Britain to those of Central Europe. It is that we may see at first-hand some of the most wonderful railway engineering in the world. The train itself will, indeed, be of but secondary importance, as our attention throughout will be concentrated on the unforgettable scenes to be witnessed from the carriage windows. We shall not, it is true, set eyes on any single engineering work of such stupendous size as the Forth Bridge, over which we rode last month; but from beginning to end of the journey we shall see the railway engineer at grips with Nature in her wildest mood, fighting his hardest to lay through the mountains a trail of steel which, when complete, is of such steepness as to oppose the greatest difficulties to operation by ordinary adhesion methods.

Switzerland is a central country in Europe, and through it have been laid some of the most important of the European trunk lines. But athwart the country, from north-east to south-west, lie two vast mountain barriers. The more northerly of the two is the narrow Jura range, and then, after we have crossed the valley of the Aare, we find the remainder of the country practically filled with the great chain of the Alps. It is the latter that constitutes the chief obstacle. The principal peaks soar upward to heights of 13,000, 14,000 and even 25,000 ft, and the passes that separate the mountain groups are often, at their lowest, more than 6,000 or 7,000 ft above sea-level. To raise the main lines of railway up to any such altitudes would be impossible, and the only method of carrying the railways under the crests of the watersheds has been that of tunnelling. It is not surprising, therefore, that several of the world’s longer tunnels pierce the Alpine chain. The Simplon, 12.3 miles; the St. Gotthard, 9.3 miles; the Lotschberg, 9.0 miles; and the Ricken, 5.3 miles, among the Alps proper, with the Grenchen-berg, 5.3 miles, and the Hauenstein, 5.1 miles, through the Jura range, are remarkable examples in Swiss territory. The Franco-Italian Mont Cenis Tunnel, 8.0 miles, and the Austrian Arlberg, 6.4 miles, are other closely-adjacent Alpine tunnels.

Even the approaches to these lengthy bores have proved in many cases a matter of great engineering difficulty. The floors of the mountain valleys up which the railways rise are irregular and uneven, and on the average they rise into the mountains at a steeper inclination than the steepest gradient up which any adhesion locomotive could pass. Very often, indeed, there are the most abrupt changes of level in the bottoms of the valleys, especially at points where the valley torrents rush through wild rapids and drop down by waterfalls.

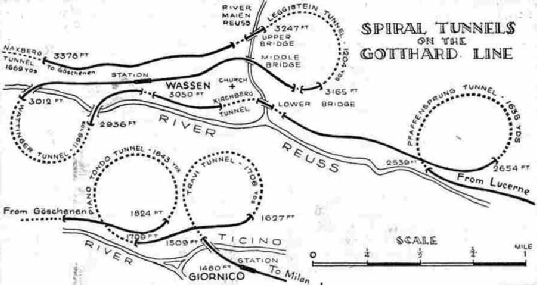

The engineer, however, must make his line rise on an even grade, and though such inclinations as 1 in 40 are comparatively common on the main lines of Switzerland, it will be seen that some of the routes that are the most notable for their engineering achieve-ments only manage to preserve such a grade as this by means of the most desperate expedients. The lines may be made to double back on themselves in order to gain altitude, or even to turn into the mountain sides and, by completely spiral tunnels, raise them-selves sufficiently to keep pace with some sudden change in the valley level.

The engineer, however, must make his line rise on an even grade, and though such inclinations as 1 in 40 are comparatively common on the main lines of Switzerland, it will be seen that some of the routes that are the most notable for their engineering achieve-ments only manage to preserve such a grade as this by means of the most desperate expedients. The lines may be made to double back on themselves in order to gain altitude, or even to turn into the mountain sides and, by completely spiral tunnels, raise them-selves sufficiently to keep pace with some sudden change in the valley level.

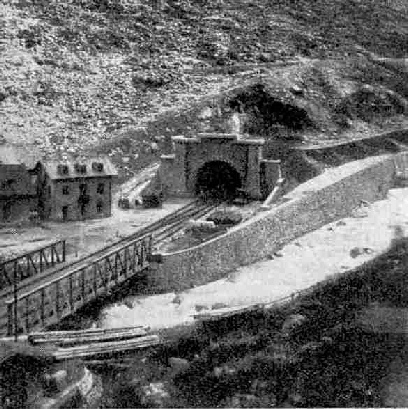

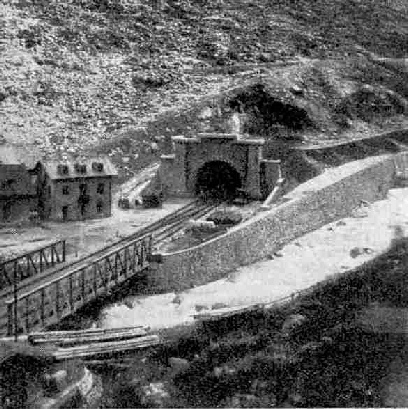

The Northern Portal of the St. Gotthard Tunnel.

It can be claimed, without fear of contradiction, that two of the Swiss main lines overshadow all the others in the boldness of their engineering. One of these is the Lotschberg line - opened in 1913 and most recent of all the Swiss main routes - threading its way from Spiez, on the Lake of Thun, southward through Kandersteg and the Lotschberg Tunnel out into the Rhone Valley, to join the Simplon route at Brigue, and so to give direct communication from Berne to Milan. The other is the St. Gotthard line, cutting straight down through the centre of Switzerland from Basel through Lucerne, Bellinzona and Lugano to Chiasso, where connection is made with the Italian State Railways, near Como. The St. Gotthard route forms the highway from Southern Germany to Milan and Northern Italy.

There are other wonder-railways in the east of Switzerland - the remarkable Rhaetian Railway system and the Bernina Railway, covering the great Canton of the Grisons - but these are single-track lines, the engineering of which was in some degree simplified by the use of the narrower metre gauge.

It is over the St. Gotthard main line that we are to travel this month, and as it is a happier experience to change from winter to spring than from spring to winter, we will make our journey in the southbound direction. First, then, we have to make our way to Basel, the northern gateway of Switzerland. We have plenty of ways of doing this, tire best and quickest of which I sampled last summer - the special Swiss night express, connecting with the 4 p.m. service from Victoria Station in London.

Leaving Calais at 7.50 in the evening, this “flyer” makes its way right across France, through Amiens, Laon (well to the north of Paris, where we pass from the care of the Nord to that of the Est Company), Chalons, Belfort and Mulhouse into Basel, at an average speed but a shade under 50 m.p.h. The 432½ miles from Calais to Belfort, indeed, are covered in 8 hrs. 38 min, at an average rate of 50.1 m.p.h. This is an object-lesson to our “Aberdonian” article, with its average rate of only 47.2 m.p.h. over the 393 miles between London and Edinburgh in both directions, and with fewer stops.

Punctual to time at 6.20 in the morning we draw into the most cosmopolitan station in Europe - the great “Bundesbahnhof” or Central station at Basel. We have nearly an hour to spare here before the departure of our train for the south, which is as well, for the railway-lover could spend days of absorbing interest in and about this wonderful railway centre. Trains are constantly arriving with coaches from every part of Eastern and Central Europe - French coaches of the Nord and Est Railways from Calais and Paris; Belgian coaches from Brussels; Dutch coaches from Amsterdam and the Hague, coaches from all the States and the principal cities in Germany; not to mention the coaches of the Swiss and Italian State Railways, returning homeward. The Swiss coaches all carry the neat legend “SBB-CFF” which indicates “Schweizerische Bundesbahnen - Chemins de Fer Federaux”, or, being interpreted, “Swiss Federal Railways” in both German and French, which are the two languages chiefly spoken in this little country.

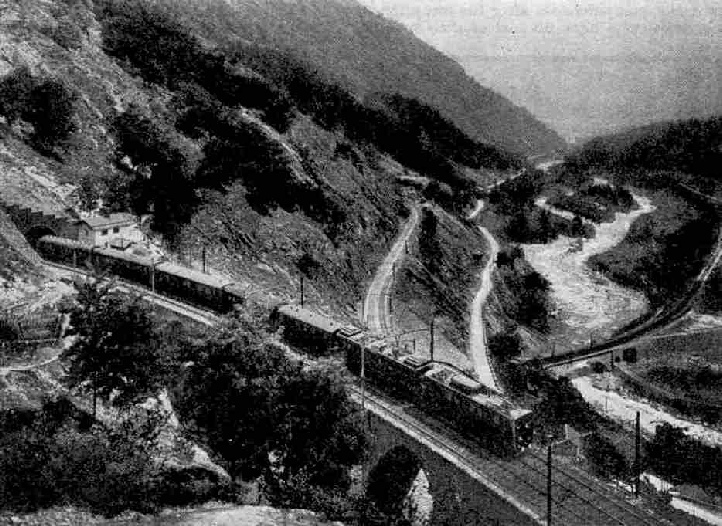

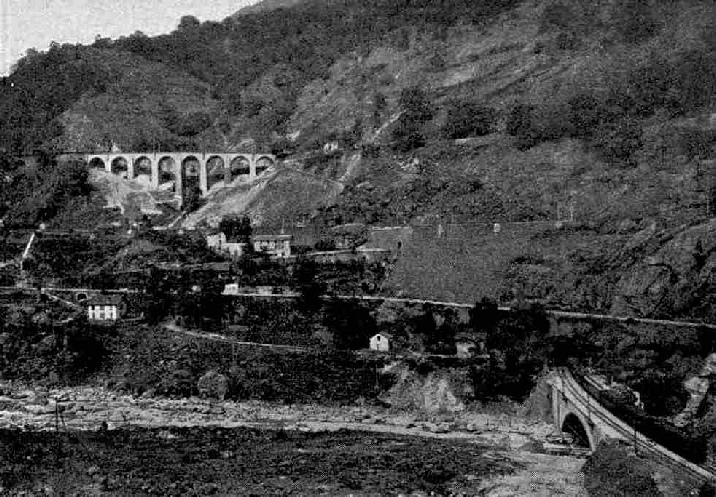

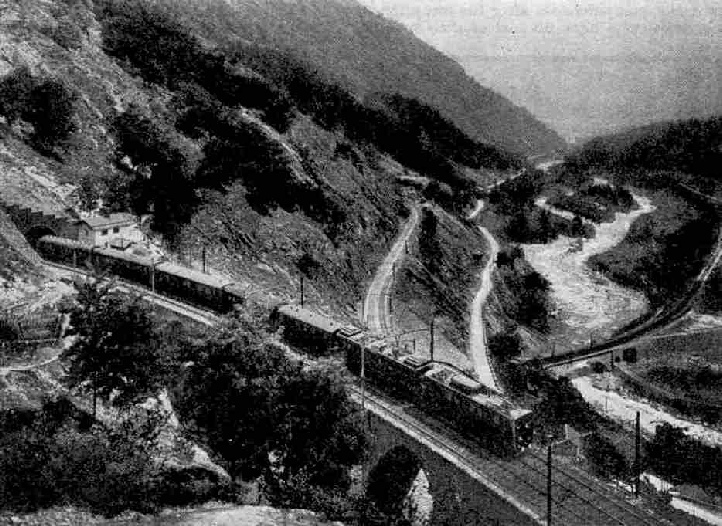

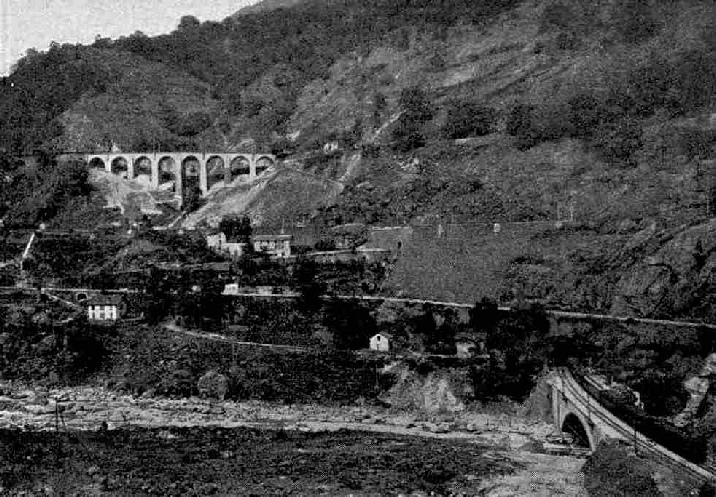

The St. Gotthard Line near Giornico (Swiss Federal Railways) as seen from above. The middle loop line is shown in the centre of the photograph, running parallel with the road.

Sleeping cars are rolling in - the “Mitropa” sleepers of the purely German “Mittel Europische” organisation, which do not proceed beyond the frontier station of Basel, and the more familiar cars of the International Sleeping Car Company, going through to Swiss and Italian destinations. The coaches bear destination boards of all descriptions - eastward to Zurich, Chur in the Grisons, Innsbruck and Vienna; southward to Milan, Genoa and Rome; and south-westward to Berne and Geneva, to name but a few.

And then we rub our eyes to see, drawn up in one of the platforms, a beautifully-appointed train in the familiar amber-and-cream livery of our own British Pullman cars. It is a Pullman train, right enough, and closer scrutiny of the cars reveals the satisfying fact that their source of origin is our own country. This is the St. Gotthard Pullman express, on which we are to travel. It is a special train, run daily in the spring and autumn seasons, while at other times in the year it is making journeys in other parts of Europe. The cars are of the 8-wheeled type whose acquaintance we have already made on the “Golden Arrow” - 77 ft in length, and for the most part weighing about 48 tons apiece. Second-class as well as first-class pass-engers are carried, on payment of the usual Pullman supplementary charge. As in the case of all the other Pullman Limited express trains of Europe, the passenger enjoys, in addition to the luxury of the travel, the advantage of faster journey times than those of any other train service during the day, as a return for the extra fare. The “St. Gotthard Pullman” in fact, is ¾-hour quicker than the best ordinary express between Basel and Milan.

The Pullman services in Europe, which are constantly on the increase to-day, are all controlled by the International Sleeping Car Company.

Before taking our places in our luxurious car, we do not fail to notice that the haulage of our train is to be carried out by electricity, and not by steam. For many decades after the inception of their first railways the Swiss, who have no coal of their own, imported large quantities front neighbouring countries, and especially from Germany, for the working of their railways. To-day they realise that Nature, whom their engineers fought so desperately in the laying of their railways, has all the time been offering them, by way of compensation, a means of working the lines that in time will render Switzerland independent of all coal supplies. This compensation is the vast store of “white coal”, or water power, perpetually available in any country which, like Switzerland, is filled with mountains whose mantles of snow and ice are always melting, under the influence of the sun, and rushing downward to the valleys.

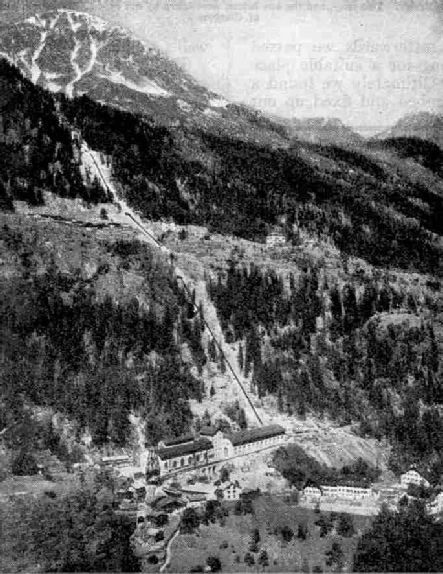

In every direction to-day these Swiss torrents are being harnessed and made to drive water-turbines; these in their turn drive dynamos and the dynamos produce electricity. For the purpose of working the railways large power-stations have been established, the biggest of which is the Barberine station in the Rhone Valley, which generates current at no less than 132,000 volts, and distributes it, by overhead transmission lines, to sub-stations all over the country. The St. Gotthard line has its own two power-stations, at Amsteg and Piotta, where current is generated at 66,000 volts. In every case there is a transformation down to 15,000 volts, which is the actual voltage of the alternating current in the overhead wires of the railway.

Some two-thirds of the railway mileage of Switzerland, including nearly all the main lines, have now been electrified, for the most part since the war; and we are to travel right across the country in the unbroken care of electric locomotives.

The replacement of steam by electricity has made all the difference to the comfort of a traveller over a line like the St. Gotthard. Before the electrification the slow uphill passage of the steam locomotives, two or three of which were often needed to a train, filled the many tunnels with steam and sulphur, making the journeys dirty and tedious. To-day we shall forge steadily upward, maintaining an even speed of but little under 40 miles an hour up continuous grades of 1 in 38½ to 1 in 40 without the slightest apparent effort.

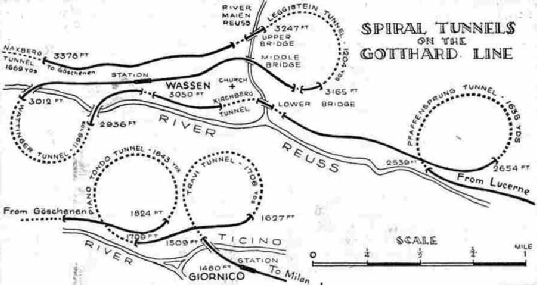

Map showing Tunnels on the St. Gotthard Line.

Punctual to time at 7.12 a.m. we are away. Drawing quickly out of Basel, over a maze of tracks, we notice on the left the enormous concentration sidings that are now in course of being laid out to deal with the exchange freight traffic between Switzerland and the neighbouring countries. Very soon we turn southward, out of the Rhine valley, and begin to ascend into the heart of the Jura mountains. These are for the most part between 3,000 and 4,000 ft in height in this part of the country, but we have to rise some 520 ft up the fertile Ergolz valley, in the first 17 miles to Tecknau, before we can get through. The original main line between Basel and Olten rose considerably higher, to a total of 920 ft above Basel at the Upper Hauenstein Tunnel (1¾ miles in length), but the altitude has now been reduced by 400 ft and the gradient greatly smoothed by the boring of the Lower Hauenstein Tunnel, 5⅛ miles in length, through which we pass in about eight minutes.

A brief downhill run and, crossing the swiftly-running River Aare, we roll into Olten at 7.48 a.m. This is the important junction between the main line from Geneva and Berne to Zurich and further east, and our main line from Basel to Lucerne, Lugano and Italy. It is of railway importance, too, as here are located the chief locomotive shops of the Swiss Federal Railways.

The first 24½ miles of our journey are now past, and have occupied 36 min; our level above the sea is 1,310 ft, as compared with the 925 ft of Basel. Least interesting of all the route, from the engineering point of view, is the next stretch, from Olten , to Lucerne, which for the most part traverses a flat plain, covered at an average rate, apart from slowings, of about 50 miles an hour. But as we approach Lucerne, given clear weather, the snowy crests of the Alpine chain begin to bear into view ahead of us, brought up on the right by the rugged mass of the mountain called Pilatus. The rushing River Reuss, of which we are to see a great deal later on, joins us on the right, and a couple of short tunnels through mountain spurs usher us into the fine lakeside station at Lucerne, 58 miles from Basel. The 33½ miles from Olten have taken us 48 minutes, and it is now 8.37 a.m.

The Lake of Lucerne - or, as the Swiss call it, “Vierwaldstattersee”, the “Lake of the Four Cantons” - is of a singular shape. It is like a cross of which the top is at Lucerne, and the two arms stretch out respectively to Kussnacht on the north-east and Alpnachstad on the south-west; while the long downward shaft proceeds eastward to Brunnen, and then takes a sudden right-angled bend to the southward, to Fluelen. At Lucerne we are in the foothills of the Alps; when we reach Fluelen we have penetrated to their heart.

To get away from Lucerne we have to retrace our tracks through the Gutsch Tunnel, to the point of divergence of the real St. Gotthard Railway, which curves right under the town in a tunnel 1¼ miles in length, and emerges on the lakeside. Owing to the peculiar configuration of the lake, the line does not follow its banks throughout, but curves round to the end of its eastern arm at Kussnacht, and from there passes round the back of the Rigi mountain, to rejoin the Lake of Lucerne at Brunnen. For sheer, breathless beauty, the view from the railway over the main “cross” of the lake, from between Lucerne and Kussnacht, in my judgment has no rival, with the fertile green pastures and the blue lake as a foreground, backed up by the dark green of the precipitous forest-clad slopes on the far side of the lake, and crowned by the eternal snows beyond.

The St. Gotthard Line near Giornico (Swiss Federal Railways) as seen from below. (Compare with view from above, shown elsewhere on this page.)

From an altitude of 1,435 ft at Lucerne, which we leave at 8.43 a.m, we rise gradually for 17 miles to Arth-Goldau. After leaving the Lake of Lucerne at Kussnacht, we hug the northern side of the Rigi, with the Lake of Zug far below us on the left. Arth-Goldau is an important junction, where a through set of Pullman cars from Zurich - the biggest city in Switzerland - is waiting attachment to our train. After this we have no publicly booked stop for 2¼ hours, during which we are to cover a distance of 88¾ miles through to Bellinzona. The stop at Arth-Goldau lasts from 9.11 to 9.18 a.m. Here we are 1,725 ft above the sea, but the line now falls until we emerge on to the lakeside again at Brunnen, to run down its southernmost stretch, through many tunnels (for the two sides of the lake are here mainly precipitous) to Fluelen.

We are about to enter the valley of the Reuss, but the first stage of the up-valley journey presents no great difficulties. It is not until we reach Erstfeld, 5½ miles from Fluelen and 37½ miles from Lucerne, that the climbing really begins. Here the single track expands to double, and so continues for the whole of the mountain section of the line.

Erstfeld was at one time a locomotive depot of importance, as it was here that the assistant locomotives were provided for the toilsome climb to the mouth of the St. Gotthard Tunnel at Goschenen. Every gradient that has been mentioned in these articles until now pales before the ruling gradient of the St. Gotthard line. From Erstfeld to Goschcnen we are to rise unbroken at between 1 in 38½ and 1 in 40 for 18 miles, during the course of which we shall be lifted 2,080 ft. Directly we leave Erstfeld we begin to rise high up the east side of the Reuss Valley; so high, indeed, that just after passing Amsteg, three miles later, we have to fly over the Karstelenbach, rushing down the branch Maderanertal Valley to join the Reuss, by the immense two-span Karstelenbach Bridge, 178 ft above the bed of the torrent. Prominent on the east side of the valley here is the vast pipe-line, bringing the water down to the Amsteg electric power-station which supplies this portion of the railway with current. A little later on we cross to the opposite bank of the Reuss by a bridge 256 ft above the water.

Now follows one of those abrupt changes in the floor level of the Reuss Valley, to which reference has already been made. Just beyond Gurtnellen, 8½ miles from Erstfeld, the river-bed “catches up” the railway, despite the ceaseless ascent of the latter. The railway thereupon turns to the right, passes into the mountain side, and winds round in a tunnel which is a complete corkscrew in shape. In the course of its length of 1,635 yards the Pfaffensprung Tunnel raises the line 115 ft, and we emerge to look right down on the line over which we were running but a few minutes before. Once again, as we are approaching the village of Wassen, the line bids fair to drop below the river level, in spite of our continued climbing. This time we turn leftward and enter the mountain side. Curving round in a half-spiral we come out again to daylight, re-cross the Reuss, and double backward past the village - returning, that is to say, in the direction from which we have come, though still steadily rising.

As we cross the Maienreuss - a branch stream - by an imposing girder bridge, we notice a railway bridge below us and another above us, crossing the same stream. Over the former we have already passed; the latter we shall cross in a few minutes. Turning again to the left into the hillside, the railway negotiates yet another spiral tunnel, and now emerges on its uppermost level, in its original up-valley direction, the engineers having lilted it no less than 400 ft opposite the village of Wassen, by this extraordinary planning. Three miles more and we are at Goschenen, 3,640 ft above the sea, and 55½ miles from Lucerne, where we shall probably make a momentary halt.

The Reuss Valley now contracts to a narrow defile, known as the Schollenen Gorge, up which it was impossible to carry the railway further. The decision was therefore reached to bore under the watershed in a straight line for miles, in order to cut through to the Ticino Valley, on the south side. It took the ten years from 1872 to 1882 in which to complete the St. Gotthard Tunnel, which was the first of the great Swiss Tunnels to be bored; it is 28 ft in breadth, by 21 ft in height, and cost in all some 57 millions of francs, or about £2,280,000. To-day, as a result of the electrification, we run through smoothly and easily in 13 or 14 minutes, and emerge at Airolo in what often seems another world. Last time I was over the St. Gotthard it was raining at Lucerne, snowing at Fluelen; there was a blizzard with snow lying deeply on the ground - like midwinter - at Goschenen, bright sun with snow higher up the mountains at Airolo, warmth and fertility at Beilinzona, and the temperature of an English early summer at Lugano - all within three hours.

Electric Train on the St. Gotthard Line at Erstfeld.

The highest point of the railway is actually in the centre of the tunnel, and is 3,786 ft above the sea. From there we steadily fall, and after Airolo there comes a resumption of the 1 in 38½-40 ruling grade, but now, of course, in our favour. Nothing much of note occurs in the first five miles of the journey, until we reach Piotta, where on the left we see another immense pipe-line coming down the mountain side straight into the Piotta power-house, which also supplies current to the railway.

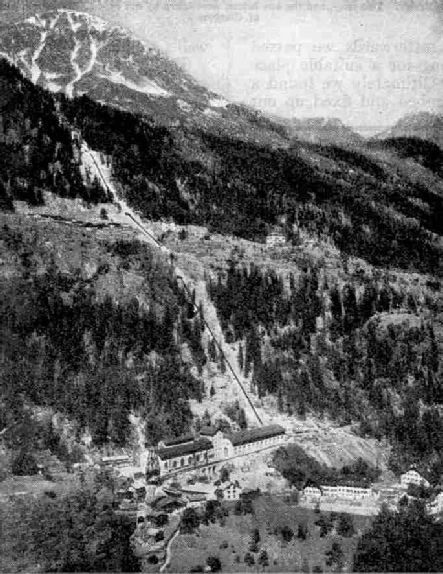

At the side of the pipe-line is one of the famous Swiss funicular railways which, in the course of ⅞-mile ascending to Ambri, carries the breathless traveller up no less than 2,145 ft with a maximum gradient of 87.8 per cent., which is rather steeper than 1 in 1¼! It claims, and not without reason, to be the steepest railway in the world, and, like most lines of a steeper inclination than 1 in 2, is worked by a steel cable.

Below Piotta, on our journey, comes some even more striking engineering than that of Gurtnellen and Wassen. From Rodi Fiesso to Faido, as the crow flies, is only 2½ miles,but the difference in level between the two places is 613 ft, and in order to overcome it the railway has circuitously to travel five miles, with a maximum gradient of 1 in 38, threading on the way two tunnels that are completely spiral. Then, as the river rushes down the Biaschina Ravine, and we approach Giornico, just before we enter Piano Tondo Tunnel, we notice a second stretch of the line below us, and a further stretch below that, the latter making its exit from the mountain-side some 300 ft below our entrance. Here there are two corkscrew tunnels - Piano Tondo and Travi, both just under a mile in length - side by side, in order that the railway may keep pace with the sudden fall in the level of the valley-floor. A downward run of 41 miles from Airolo brings us to Bellinzona, where we have fallen to a level of 760 ft, or just over 3,000 below the level of the St. Gotthard Tunnel. The time is now 11.35 a.m. and the stop lasts but two minutes.

Bellinzona is the junction for the historic town of Locarno, which we see, some miles off, on the shores of Lake Maggiore, as we ascend to the mile-long Monte Ceceri Tunnel that carries us under the watershed separating the Ticino Valley from that of the Lake of Lugano. This has necessitated a fresh ascent of 800 ft in 8¾ miles, once again on single line, to Rivera (1,560 ft), after which we drop a corresponding distance, down the fertile Vedeggio Valley, to lovely Lugano, where the station is high above the lake and 1,010 ft above the sea. The time of the halt here is from 12.7 to 12.10 midday.

Skirting the shore of the lake, by means of tunnels and bold viaducts, we descend to the lakeside at Melide, and then cut clean across the lake by a remarkable causeway to Bissone. Here we are down to 900 ft, but another rise of 280 ft ensues in the next six miles, ere we can drop to the frontier station at Chiasso, reached at 12.34 p.m.

Within Swiss territory the “St. Gotthard Pullman” has now travelled for 198 miles, of which 140 miles have been over the marvellous St. Gotthard route. In the course of this latter distance it has passed through 80 tunnels whose aggregate length is 28½ miles, and over no less

Within Swiss territory the “St. Gotthard Pullman” has now travelled for 198 miles, of which 140 miles have been over the marvellous St. Gotthard route. In the course of this latter distance it has passed through 80 tunnels whose aggregate length is 28½ miles, and over no less

than 324 bridges of more than 32 ft span, many of them viaducts of no inconsiderable size. Small wonder is it that the total cost of the St. Gotthard line was nearly three hundred million francs, which represents about twelve million pounds.

The Power-plant of the Swiss Federal Railways at Barberine.

At Chiasso the Swiss Federal authorities hand us over to the care of the Italian State Railways, after the Customs authorities have taken 18 minutes in which to examine our baggage, and a run of 32 miles, through Como, where a 2-minute stop is made, and across the Plain of Lombardy, brings us 63 minutes later to the great city of Milan. It is 1.55 p.m. and our journey of 230 miles, over these terrific gradients, has taken us 6 hrs. 43 min, whereas the very quickest journey possible - between Basel and Milan in pre-war days was 8 hrs. 5 min. This shows how remarkable are the advantages derived by the passenger from the electrification.

The “St. Gotthard Pullman” has not yet finished its day’s work, however. At 4.5 p.m. the same afternoon, it will be starting northward again out of Milan. Six o’clock in the evening will find it at Lugano and 9.15 at Lucerne; while the tired roiling stock, after 460 miles of travelling, will find its way into the great Central Station at Basel at 10.44 p.m. at night, there to disgorge its passengers into the night expresses leaving for all parts of Central and Western Europe.

You can read more about “The Glacier Express”, “The Great St Gothard” and “Through the Bernese Alps” on this website.

You can read more about “Alpine Tunnels” in Wonders of World Engineering

The engineer, however, must make his line rise on an even grade, and though such inclinations as 1 in 40 are comparatively common on the main lines of Switzerland, it will be seen that some of the routes that are the most notable for their engineering achieve-

The engineer, however, must make his line rise on an even grade, and though such inclinations as 1 in 40 are comparatively common on the main lines of Switzerland, it will be seen that some of the routes that are the most notable for their engineering achieve-

Within Swiss territory the “St. Gotthard Pullman” has now travelled for 198 miles, of which 140 miles have been over the marvellous St. Gotthard route. In the course of this latter distance it has passed through 80 tunnels whose aggregate length is 28½ miles, and over no less

Within Swiss territory the “St. Gotthard Pullman” has now travelled for 198 miles, of which 140 miles have been over the marvellous St. Gotthard route. In the course of this latter distance it has passed through 80 tunnels whose aggregate length is 28½ miles, and over no less