© Railway Wonders of the World 2012-

The Railway in War

Railways in Wartime During the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

DERAILED ARMOURED TRAIN at Kraaipan (1899)

WHEN we consider the stirring events that have taken place during late years it seems a far cry to the conflicts which preceded the Great War, dwarfing them, so to speak, into puny insignificance. It may be interesting, however, to view from a distance the part the locomotive took in them. At the outbreak of the Boer War there is the scene at the English station, where the Regular, Yeoman or Volunteer is bidding farewell to those he loves; a scene of deep sorrow underlying all the cheers and handkerchief-

Early in the war we read of trains packed with English fugitives from Pretoria and Johannesburg -

Whichever way we look, or to whatever period of the war, the railway looms large, for it was in many districts the sole means of transporting troops and supplies. The very first act of hostility was the derailment by the Boers of a train at Kraaipan. For months the sound of dynamite, doing its fell work on culverts and railway bridges, was heard. Every other day we read of a train being derailed and burnt, after the mails had been scattered to the winds, and of the exploits of armoured trains. At Mafeking an engine laden with explosives is sent flying along the track towards the besiegers. From Pretoria the President escapes over the railway to the ship awaiting him at Delagoa Bay. Far up in Rhodesia men are being painfully transported from Beira to Salisbury along the ricketty narrow gauge, and southward to the relief of Mafeking. When the tide turns in favour of England the engineer gets to work, mending the ruined culverts, replacing the shattered bridges, clearing the ruined tunnels. Engines and rolling-

A hard task indeed fell to the lot of the men who had to watch, organise, and control the railway traffic. There was no class more worried and worked than the railway staff-

Thirty years before the Boer War a very similar state of things was existent in France, when the Germans and French were locked in the most terrible conflict known till then. The Germans have pushed their armies across to Paris and are feeding them, reinforcing them and supplying all the munitions of war over the railway. Bridges and tunnels have been blown up; desperate men have struck desperate blows for their country by wrecking trains; but the conquering flood still rolls on. There is the same tremendous activity at the railway depots.

“Apart from its importance, there was not a more interesting place in the whole of the occupied country than the Nancy railway station. At that great crossroad on the highroad of the invasion, where the Saarbruck-

The importance of keeping open their railway communications was such that the Germans took a very strong line with would-

The invaders brought with them five railway detachments, whose business it was to repair any damage done to the line by the invaded. These detachments consisted of navvies and engineer troops. When the army advanced they reconnoitred the lines, removed obstructions, restored broken bridges, adapted the existing stations to military purposes, built new stations where required, and directed the traffic. In case of a retreat, on them devolved the role of destroying the track sufficiently to impede the enemy.

At Nancy engines of all kinds had been collected in large numbers. French and German locomotives jostled one another on the four main lines and in the innumerable sidings. “At times every inch of line”, says Mr. Sutherland Edwards, “was covered, and the trains extended half a quarter of a mile beyond the station each way. To look for any particular train was like looking for a carriage on Epsom Downs; but you could make your search if you liked; . . . you might walk between the trains, cross between the carriages, jump into a carriage while the train was in motion, jump similarly out of it, keep the carriage doors open or shut as you felt inclined, do anything in short except drive the engine.”

French engine-

As soon as the Germans had a firm grip on a length of railway they proceeded to send artillery over it for the siege of Paris. Hundreds of guns of all weights and ages were loaded into trucks, along with suitable ammunition, of which huge quantities were expended before the capitulation of the metropolis. Here and there, in the neighbourhood of a town, and therefore within reach of its guns, the railway had to be deflected on to a temporary track which “turned” the obstacle, since the guns must be brought up at all costs. In October 1870, 230 pieces of artillery from Germany were delivered at Nanteuil, whence they were distributed by road to the various positions surrounding Paris.

The Germans had one great advantage over the English as regards the use of a railway as a means of support, in that, supposing the track had been destroyed, they would still have the excellent roads for which France is famous to fall back upon. As we know so well from printed accounts and photographs, South African roads are alternately dust trails and quagmires, punctuated by terribly difficult “drifts”, through which long teams of oxen painfully hauled waggons and artillery. Furthermore, our troops were not able to “live on the country” as did the Germans. They could not requisition food when there was no food. For sustenance, they depended entirely on the railway.

In turn, Russia’s present position is infinitely more precarious than that of Britain at any period of the Boer War. For five-

Contrast with these facts the case of Russia in her struggle with Japan. She possesses one possible means of comm-

On account of the secrecy observed by the Russian authorities with regard to the management and fortunes of the line, little reliable news was allowed to filter through. We were fully aware of the strenuous efforts needed to hurry large numbers of fresh troops into Manchuria, and to feed them, if the Russians were to have any chance of ultimate success. The situation centred on the railway; if it proved utterly unequal to the strain cast upon it, Russia’s hold of Manchuria was gone. As a correspondent of the Daily Express put it: “It [the railway] is the artery of the war. If the accident of nature or the schemes of the Japanese should fasten a ligature upon it, the Russian cause in the Far East must perish.” History has shown the truth of the prediction.

Apart from its importance, then, there is nothing much to be said of the Trans-

It soon became evident that for a really serious destruction of railway property the destroying force must occupy the line for a considerable period; and some desperate fighting was witnessed before the stronger party finally managed to tighten its grip on a railway. Then the destroyers set to work in earnest, showing, as has been said, almost as much ingenuity in preparing means for its ruin as had previously been evinced in its erection. Military writers of the United States ordered that not only should the piles and woodwork of the bridges be smeared with tar, but shells and grenades with fuses of various lengths should be arranged to keep up recurrent explosions, in order to prevent any attempt of the enemy to extinguish the fire. In case of a bridge being inaccessible, heavy timber rafts were to be sent down the current to smite them like battering rams; and if these failed, fire vessels should be tried, or floating torpedoes exploded by electricity.

The siege of Atlanta, where the Confederate army had taken up its position against General Sherman, was brought to a successful issue for the Federals only after Sherman had effectually severed the railways connecting Atlanta with the Southern States. The general in person superintended the work of demolishing the track. “For twelve and a half miles,” writes one of his staff officers, “the ties were burned, and the iron rails heated and twisted with the ingenuity of hands old to the work. Several cuts were filled up with the trunks of trees, logs, rocks, and earth, intermingled with loaded shells, prepared as torpedoes, to explode in case of an attempt to clear them out.”

In the neighbourhood of Atlanta one of the most stirring events of the early part of the war was enacted; and as its scene was the railway, it may suitably be described in some detail.

In March 1862 the Federal and Confederate armies were approaching each other in Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama. The former, under General O. M. Mitchell, occupied Nashville and Shelbyville on the line running south from Louisville and Cincinnati. The Confederates, who were pushing up northwards, had their base at Atlanta, and held the railway which put that town, via Chattanooga, in communication with Corinth in the west and Richmond in the east. It was along this line -

Some men therefore volunteered to enter the Confederate lines in disguise and work their way down the railway to Atlanta, where they hoped to be able to capture a locomotive and return north, burning and blowing up bridges as they went, and otherwise rendering the track useless. They reached Atlanta safely, but owing to the absence of the engine-

The leader, Mr. J. J. Andrews, a Kentuckian, did not give up hope. He asked for a larger number of men to help him in a second attempt, and in response so many volunteers came forward that he was able to select twenty-

On his first expedition Mr. Andrews, a man of fine presence and one who, by his manners and bearing, could easily pass himself off as a cultivated southern landowner, had possessed himself of a time-

After many adventures the gallant twenty-

The men were to embark on an early morning train and travel in it as far as Big Shanty, where it halted to allow the passengers to get some breakfast. Then would come the chance of uncoupling the engine and a few cars from the rest of the train, and making off with them.

This programme was carried out to a nicety. When the conductor, engineer, fireman, and passengers had adjourned to the refreshment room, the conspirators quickly distributed themselves into their allotted places, and before a cry could be raised the locomotive and three cars were speeding northwards on a journey such as has never been paralleled in railway annals.

The steam soon gave out, and it became necessary to halt and replenish the furnace with wood. The fugitives built their chief hopes upon the difficulty that the Southerners would experience in getting hold of an engine to send in pursuit. At Kingston, thirty miles north of Big Shanty, they would meet an irregular train, and, that once passed, they expected to run at top speed for the nearest bridge, burn it, and hurry on, serving every other bridge they crossed in a like manner. As they went they would destroy the telegraph, so that no messages could be flashed back to Atlanta.

Keeping on regular time, they reached Kingston, two hours after the capture of the train, without having in any way damaged the line. As their own train had been scheduled as irregular, Andrews claimed to be a Confederate officer of high rank, who was running a special powder-

Unfortunately, the local southward-

To wait would have been fatal. Andrews decided to risk a collision, and ran his train on to the main line. A minute later it was flying north at forty miles an hour for Adairsville, in the hope of reaching that station before the expected freight. A short distance south of this station the train stopped, and the men dismounted to cut the wires and remove a few rails, which were loaded on the cars along with some sleepers that happened to be stacked there. At Adairsville they met and passed the expected freight, and a passenger train at Calhoun. The road then lay clear to Chattanooga. Their hopes rose.

A little north of Calhoun was a bridge spanning the Oostenavla River which they had determined to burn. As a precautionary measure, Andrews decided to remove a rail to obstruct pursuit by any of the trains which had been passed. They had just wrenched this free when, to their dismay, they saw an engine bearing down upon them! The pursuit had indeed been pressed hard!

We must now return to Big Shanty, and briefly follow the doings of Fuller, the conductor of the captured train.

As the locomotive left the platform, Fuller and two companions pursued it on foot amid the jeers of their companions. He expected that the fugitives would abandon their prize as soon as they had cleared the Confederate outposts, and he therefore hoped to be able to retake the engine and bring it back to his train. But some severed telegraph wires soon undeceived him.

The three fell in with a party of workmen and a hand car. These were at once pressed into the service, and the pursuit now continued at seven or eight miles an hour. Their one hope of success rested on finding at Etowah, 13 miles from Kingston, an engine which worked a branch line to some ironworks. Great was their delight when they saw the old “Yonah” standing in the station, its head turned towards Kingston. On to it they sprang, and their former crawl quickened into nearly a mile a minute. But when Kingston was reached the birds had already flown. Here they changed engines, and with a force of a hundred armed men continued the pursuit until, beyond Calhoun, they sighted their quarry.

Transferring our attention once more, we will join Andrews and his party.

As they had a rail removed between them and their pursuers, they hoped to be able to burn the bridge before the damage could be put right. But Fuller’s train managed, in an almost miraculous manner, to clear the gap and continue merrily on its way. The driver attributes this extraordinary feat to the fact that the blank occurred in the inside rail and on a curve. As the train was travelling at a very high speed its weight was thrown mostly on the outside rail, and kept up against it by centrifugal force. With quick decision he increased the speed, and after a sharp jolt the engine and its cars were on the farther side of the gap. Had Andrews removed an outer rail, the whole history of subsequent events would have been altered.

Seeing that it was now impossible to fire the bridge, the brave Northerner cast loose a car in the hope that it might wreck the pursuing engine. But Fuller pulled up in time, and, picking up the car, proceeded, pushing it before the engine. A second car was then dropped, with as little effect.

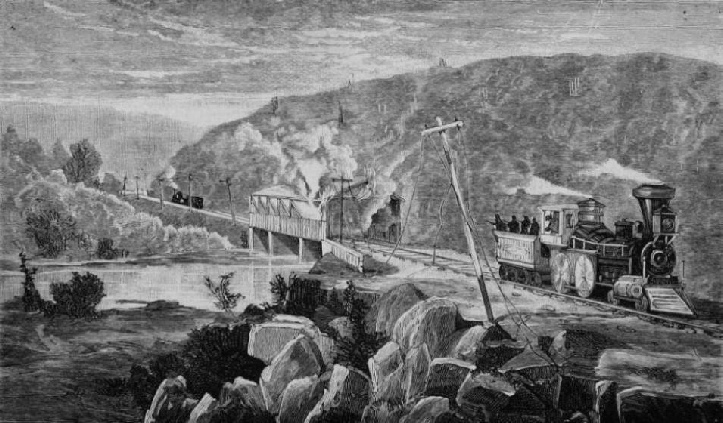

The “Great Locomotive Chase” during the American Civil War

The fugitives next proceeded to throw the sleepers they carried on to the track, and so managed to impede the “Shorter”, as the other engine was named. Short halts were made to cut the wires and take in water and fuel. As long as the pursued had anything on board which could be used as an obstruction, the pursuers were obliged to keep at a respectful distance -

Thus the chase continued mile after mile at express speed. Idlers in the stations were amazed by the sight of a train dashing past closely followed by another. To the travellers the country appeared to spin past giddily; then the leading engine would be suddenly reversed, and the brakes applied with such suddenness as to cause the occupants of the one remaining car to cling tightly to its sides. Scarcely had the wheels ceased to revolve when the Northerners were on the track, desperately loading ties or cutting the telegraph wires. At the signal all sprang aboard again, and the engine bounded forward once more at such a pace that it was a wonder how it kept on the rails at all.

Mere speed could not, however, save Andrews’ party from an even swifter engine. Not far ahead of them now lay Dalton, a junction for the lines running east and west. It was the southern apex of a triangle of lines, the other two corners being at Cleveland and Chattanooga. If they managed to clear Dalton it would be of no avail, since news of the flight would reach Chattanooga via Cleveland before the locomotive. However, they passed Dalton unmolested, and soon entered a tunnel where they determined to play their last card. With great difficulty they set the car ablaze, and cast it adrift on a long covered bridge. The other party simply pushed it ahead to the next siding and left it there to burn.

Little now remained but to abandon the railway, and make for the Northern Army across country, through the woods and mountains. Some of the bolder spirits did, indeed, suggest that it would be worth while to form an ambuscade near an obstruction, and, while the pursuers were hard at work, to fire upon them, board their train, and send it flying back to collide with the one following behind. But Andrews overruled the suggestion, and the flight continued at a slower speed, as the supply of fuel now began to fail. Twelve miles from Chattanooga the fugitives reversed their engine, jumped off, and left it to do any evil that the exhausted furnace could urge it to. Fortunately for those behind, the “General’s” force was expended, and it came to a standstill before reaching them. With the subsequent adventures of the brave twenty-

A Southern journal says: “We doubt if the victory of Manassas or Corinth were worth as much to us as the frustration of this grand coup d’etat. It is not by any means certain that the annihilation of Beauregard’s whole army at Corinth would be so fatal a blow to us as would have been the burning of the bridges at that time and by these men.”

The pluck shown by Andrews and his comrades was equalled by the determination of Fuller and his party. The people who at Big Shanty mocked the conductor as he pursued the train on foot little knew that that pedestrian feat was to avert a great disaster from the Southern arms. Fuller thoroughly deserved all the credit he got.

Note: For a more detailed description of this incident, the reader is referred to Capturing a Locomotive by the Rev. W. Pittenger (1885), who was himself one of Andrews’ associates.

You can read more on “The General”, “Railways at War 1” and “The Trans-