A Famous Train of the South African Railways

FAMOUS TRAINS - 37

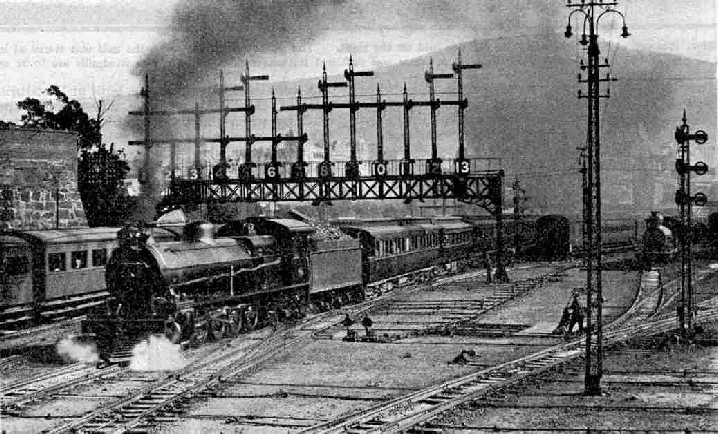

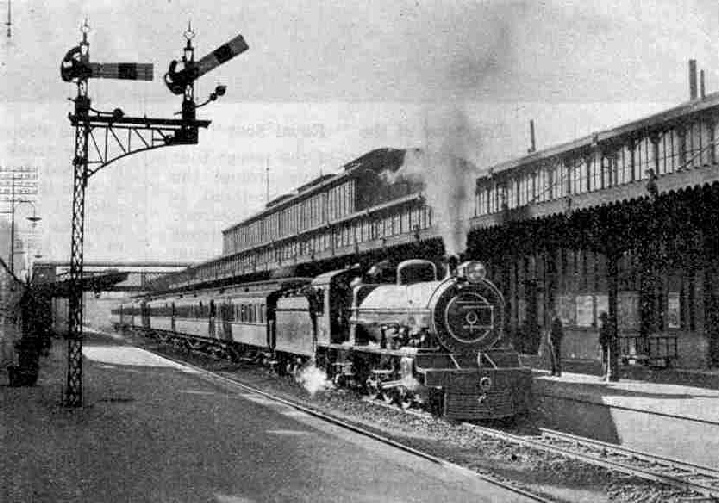

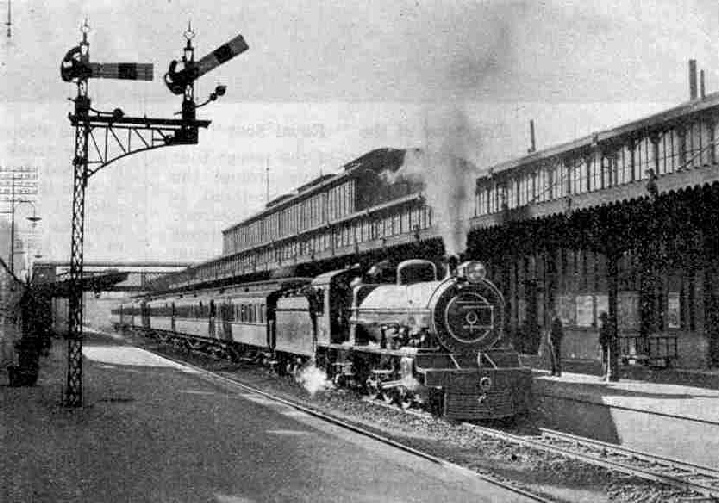

The “Union Express” leaving Capetown with 4-8-2 locomotive. Note the electric headlight, with dynamo.

ONCE again those travelling bags of yours will be in request this month, for we are to make an even longer journey than that which took us across the Atlantic to Canada, and yet further over the American Continent to Vancouver. Another of the British Dominions now claims our attention.

Over the 16-day sea voyage from Southampton we have no time to dwell, but the ship that has brought us from England is lying at anchor in Table Bay, under the shadow of the singular and characteristic shape of Table Mountain - the landmark of the Southern Seas, as it has been called. Very likely on the morning of this day it is wearing its “table-cloth” - a mass of flat cloud or mist wrapping itself round the flat top of the mountain. But we shall have little time for the beauties of the Cape, which might well occupy us for days; for as soon as we set foot in Africa we are going to board the train that is to take us up-country for the best part of a thousand miles from the city of Capetown. From the morning of to-day till the evening of to-morrow we shall be comfortably ensconced in the “Union Express” of the South African Railways, on our way northward to Johannesburg, or “Jo’burg”, as it is often affectionately called by the South African.

This being Monday morning, the day of the arrival of the mail steamer from England, the South African Railway authorities have kindly sent the “Union Express” down to the docks to fetch us. Only on Mondays and Fridays does this famous train run. On Friday mornings it starts direct from the main terminus of the S.A.R. in Capetown at 10.45 a.m, but on Mondays from the Docks at 10.15, leaving the Monument Station, on the suburban lines, half-an-hour later, at 10.45. It is a strictly limited train, carrying first-class passengers only, and unless we had been farsighted enough to secure our places before-hand there might have been some doubt as to whether we should have got on board at all. But it is well worth our patronage, as the next train up-country does not leave until four o’clock in the afternoon, and takes all but 10 hours longer on the trip of 956 miles than our “crack” express.

In spite of my use of the word “crack”, however, we need not look forward to anything in the way of high speed. For reasons that you will appreciate presently, the overall time of 29¾ hours entails an average rate, stops included, of 32 miles per hour. On the return journey this time is cut to just under 28½ hours. Both figures are an enormous advance on the time of 44¾ hours that operated before the Union of South Africa came into being in 1910, since when unceasing progress has been made by the South African Railways.

Probably, before we take our places in the train, the track over which we are to run will attract our attention. It is possible that you saw the South African train when it was on exhibition at Wembley in 1923 and 1924; you may, indeed, have had lunch or dinner in its excellent restaurant car. But if not, your astonishment will be excusable when you find that you are to travel in vehicles that are slightly lower on the wheels, perhaps, but in length and width just as big as those to which you are accustomed at home - over a gauge but three-quarters of the British standard figure of 4 ft 8½-in. The first beginnings of railways in both the Cape and Natal, in 1859, were on the 4 ft 8½-in gauge, but when the mining areas in the interior of South Africa began to be developed and railway communication with the sea became imperative it was realised that to connect the interior with the coast on the wider gauge would be an unjustifiable expense. A narrower gauge would allow much more latitude in the engineering, enabling the engineers to employ a sharper curvature and to carry their lines round the contours of the mountainous intermediate country, thus saving much cost in the matter of cutting and embanking, bridging and tunnelling.

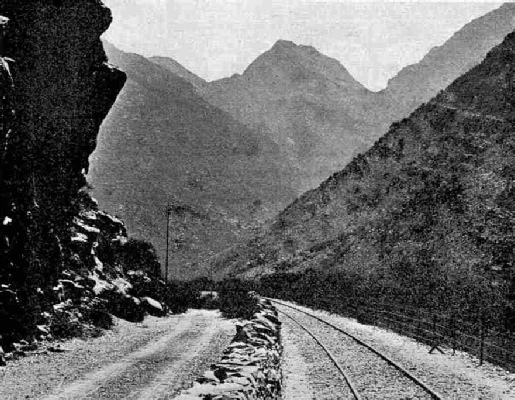

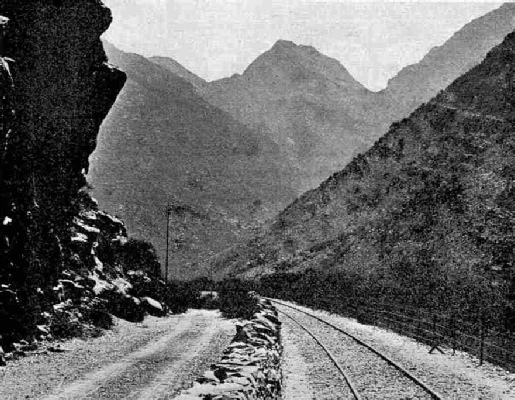

Entering the Hex River Pass.

Consequently it was decided to use a gauge of 3 ft 6-in, which has served South Africa well, and is now in practically universal use south of the Equator. Should the dream of Cecil Rhodes ever materialise in the shape of through railway communication from the Cape to Cairo, it will not be possible for the “Union Express” to make the through journey, as the railways of Egypt are laid to the standard gauge of 4 ft 8½-in. But as yet more than 1,000 miles of largely unexplored country lie between Bukama, in the Belgian Congo, most northerly point of the railway systems in South Africa, and Sennar, on the Upper Nile,which represents the most southerly tentacle of the railways of the Soudan, before the through railway route becomes an accomplished fact.

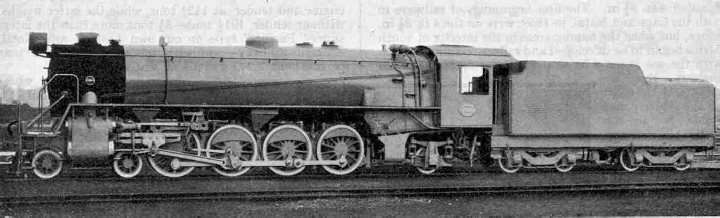

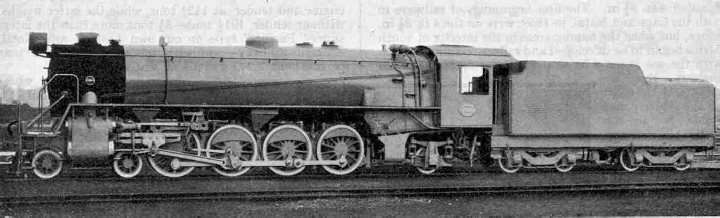

Despite this limitation in gauge width, the South African Railways now mount on their tracks locomotives of greater size and weight than the biggest in Great Britain. In all probability we shall find at the head of our train a powerful “Mountain” (4-8-2) type locomotive, with eight-wheeled tender, either of the “15 A” class, which is seen in the picture of the “Union Express” leaving Capetown, or of the later Baldwin-built type. The former turns the scale, engine and tender, at 142¾ tons, while the latter weighs, without tender, 101½ tons 5½ tons more than the latest super-“Pacific” type on our own London and North Eastern Railway - and with tender, carrying 12 tons of coal and 7,200 gallons of water, 166¾ tons.

A coupled wheel diameter of but 4 ft 9-in clearly indicates that tractive effort rather than speed is desired. The fastest runs in South Africa that I have been able to trace do not exceed an average speed of 40 m.p.h. between stops, and 30-35 m.p.h. is the more common figure. If we touch so much as 50 m.p.h. at any point we shall be doing well. Why, then, the need for this tremendous tractive power? We shall not be far on the way out of Capetown before the reason will be apparent. Striking external features of the engines are the “cow-catcher” and the powerful electric headlights, which generate their own current. Both are reminders that in a country like South Africa railways are not fenced, and provision must be made for seeing possible obstructions and dealing with animal “trespassers” on the line.

Our train is made up of first-class coaches, a restaurant car, and a van or two for baggage and mails. The coaches are each 63 ft in length and are divided into five ordinary compartments and three half or coupé compartments apiece. Every compartment has its own wash-basin, with hot and cold water laid on, which we shall find of no small use on some of the dustier parts of the journey. The width of the coaches is 8 ft 9-in, which is within a few inches of our British width dimension, but these first-class compartments are not arranged to hold more than two a side, so that we have plenty of elbow-room. The dining-car, it is interesting to find, is a “twin” coach articulated on the Gresley principle. One of the two coach-bodies is the large open dining-saloon, and the other contains the kitchen and pantry, and sleeping compartments for the restaurant car staff who, like ourselves, are going to sleep on board. And, by the way, if we want to be economical, we can go to the chief steward on the restaurant car, before we start, and obtain from him a book of tickets covering all the meals on the journey, by which procedure we shall save two shillings a day!

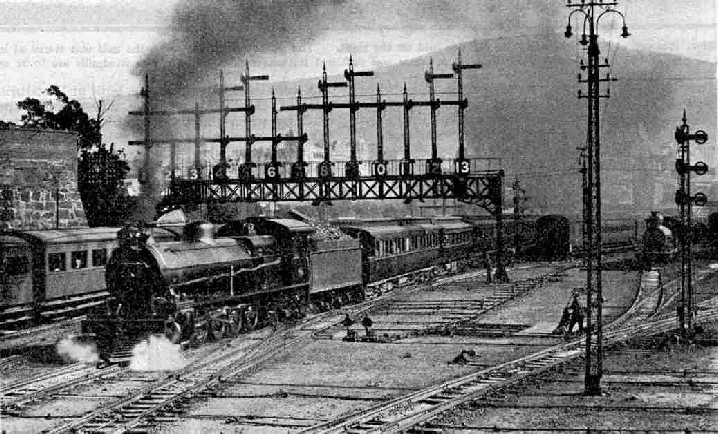

There is a very busy suburban train service round Capetown, of which we shall see plenty of evidence shortly after starting. The busiest routes are those from the Monument Station to Sea-point, and from the main station to Wynberg, the Cape Flats line, and over the main line to Bellville, all of which have train services throughout the day at 15-minute intervals or less. The number of suburban passengers carried in the year amounts to well over twenty millions, and a start has been made with the work of electrification. At the Monument Station we shall see that the Sea-point suburban trains are already being worked electrically, and work is now proceeding rapidly on the 22-mile stretch through Wynberg to Simonstown.

Promptly at 10.45 a.m. we are away from Monument, on our journey northward. Soon we are passing Salt River, a busy suburban junction with a power-operated signal-cabin, where the Wynberg and Simonstown line leaves us; and at Maitland, a short distance farther on, we part company with the Cape Flats line. Talking of signals, we shall not have failed to notice that in South Africa the semaphore arms rise into the “upper quadrant” when pulled off, instead of falling; ere long this is to be the standard in Great Britain also. Bellville is another important junction where a couple of lengthy branches diverge, one to Saldanha, on the west coast, and Bitterfontein, 289 miles out of Capetown; and the other going eastward over the Sir Lowry Pass to Caledon and Bredasdorp, 156 miles out. The mountains of the Cape Province are in view ahead of us, and already we have begun to rise; in the 15 miles from Maitland to Kraalfontein we ascend all but 300 ft. This, however, is only a beginning.

The first stop is at Wellington, 45 miles out of Capetown, which we must clear at 12.3 p.m, 78 minutes after starting, the booked start-to-stop speed being about 36 m.p.h. Next comes a stop at Wolseley, 40 miles on, at 1.22 p.m; at Porterville Road the line, which has been heading northward through the hills, bends completely round to a south-easterly direction for some distance. Through Worcester, an important junction, we pass without stopping, now at a level of 795 ft, 109 miles from Capetown, and with the mountains closing in ahead. At Hex River, 15 miles farther on, and 1,275 ft above the sea, climbing begins in real earnest. In the course of the next 21 miles, through the Hex River Mountains, we are to ascend to an altitude of 3,147 ft at Matroosberg. For mile after mile the engine toils unceasingly upward; the “ruling” or steepest gradient is 1 in 40, and the curves sharpen to a minimum radius of 330 ft. Advantage is taken of every kloof and ridge to obtain the development of the line necessary to overcome these great differences in altitude. Travelling “up-country” takes on a new meaning in South Africa. It is “up” in every sense of the word, as the whole of the interior consists of one vast plateau, varying in height from a minimum of 1,820 ft, at roughly 300 miles from Capetown, to no less than 5,735 ft at the termination of our journey. On to this plateau we are now ascending. The speed is naturally reduced by the ascent. Between De Doorns and Touws River, the next two stops, 84 min. are allowed for a distance of 31 miles, or an average of 22 m.p.h; but this is not to be despised when the average up-grade for 21 miles has been steeper than 1 in 60!

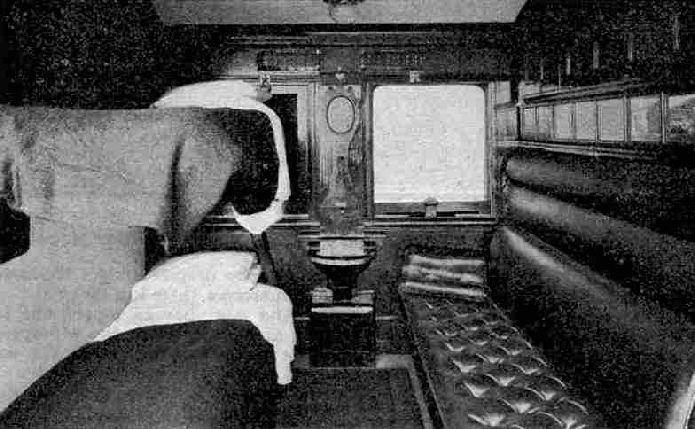

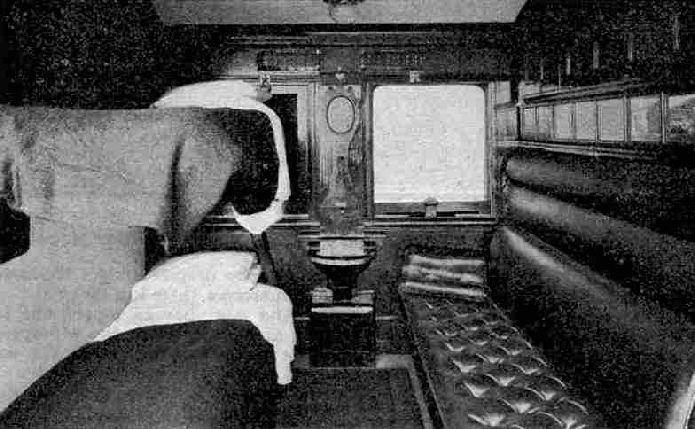

First-Class compartment of the “Union Express”. The two beds have been made up on the left hand side of the compartment.

And now, having topped the summit of the Hex River Pass, we find ourselves in the widespreading Karoo. We shall not at first be enthusiastic about the scenery. There is little stirring, and not much appears to grow. A lonely farm is seen here and there, and an occasional plantation, but very, very little water. There is no stint of sun, hour after hour and day after day, and the dry thin air will soon begin to invigorate us, even though the sun-swept, drab and lonely scenery at first may fail to interest. Sundown is now approaching; the stunted bush is growing dusky; bush-fires blink in the background; the Karoo will soon be asleep. We begin to think of sleep, too; and for the first time, perhaps, we realise that we have not so much as seen a sleeping car on the train. Presently the mystery will be solved.

We have had two longish evening runs - an hour-and-three-quarters over the 53 miles from Touws River to Laingsburg, and a still longer one for four hours over the 126 miles from there to Beaufort West. The latter is the longest break on the whole journey without any publicly-booked stop, although quite possibly we shall have had service stops, as the whole of our route, except in the neighbourhood of the large cities, is single line. During the course of this last run we have dined, and on leaving Beaufort West at 9.53 in the evening we are ready for bed.

Along comes one of the train attendants and proceeds to transform the very compartment in which we are riding. It is a compartment by day and a bedroom by night. Comfortable beds are made up on the two seats, on each side of the compartment, and then there are let down, above them, the two side partitions of the compartment, making two upper berths. Our compartment now contains four beds, one for each occupant, unless we have been fortunate enough to obtain one of the coupé compartments, in which case there are only two beds.

What the “bedroom” looks like is made clearly apparent in one of the accompanying photographs. It is of the more interest to us in that in the autumn of this year three of the British railway groups are to introduce sleeping cars of this type for third-class passengers on the long night journey. Beds will not be made up in the British cars, however; they will simply give facilities for four passengers to lie at full length in each compartment.

In long-distance trains that convey second-class passengers the same type of car is used, but three berths, one above another, are squeezed in on each side of every compartment, instead of the two in the first-class. The South African Railways charge little enough for making you comfortable, too - three shillings is the modest exaction for the use of the bedding, whether you use it for a single night or, on the longer journeys, for two.

So, for the present, goodnight! Things will be happening during the dark hours of which, doubtless, we shall be blissfully unconscious. We shall stop at Hutchinson, and then, at 2.40 a.m, in the very “small hours”, we shall reach the important junction of De Aar. From De Aar there goes north-westward to Upington a branch line which, after crossing the Orange River by means of the longest bridge on the South African Railways - 102 steel spans with a total length of 2,974 ft, more than once totally submerged by great floods, but without damage - joins the system of what until the Great War was German South-West Africa. This has now been taken over by the South African Railways, and the “branch” from De Aar to Upington, Windhoek, Swakopmund and Walvis on the west coast, has a modest length of 1,134 miles! So uninhabited is much of the country traversed that there is only one passenger train from De Aar to Walvis, and that only runs twice a week! Even over the important main line by which the “Union Express” is now travelling, for a large proportion of the distance there are not more than three daily passenger trains.

De Aar, 501 miles from Capetown, is one of the most important locomotive depots on the route, and it is quite likely that our locomotive will be changed here. The tractive power required for working over the Karoo is not so great as that needed in the climbing of the Hex River Pass, and our large “Mountain”-type engine may now have substituted for it a Baldwin-built “Pacific”, with larger driving wheels. Not that the Karoo is entirely flat, by any means. From the lowest point at Fraserburg Road, 1,820 ft above the sea, we climbed 2,355 ft to Hutchinson, in 129 miles, but from De Aar onward we shall remain at a fairly even level of between 3,500 ft and 4,100 ft for the next 250 miles. Fraserburg “Road”, by the way, is 92 miles from Fraserburg!

Dawn has broken when we stop at Orange River. The dining car stewards have plied us with early morning tea, and we have washed and dressed and are feeling distinctly ready for breakfast when the “Union Express” draws into the famous mining town of Kimberley, 647 miles from Capetown. The time is 6.47 in the morning, and we have been 20 hours on the way. Probably there is no other piece of land of comparable size in the world from which has been wrung such wealth as from 200 acres at Kimberley. Four mines in this small area have produced, in 50 years, diamonds worth 255 millions sterling! The peerless “Star of South Africa” - a single stone valued at £25,000 - was picked up on the banks of the neighbouring Vaal River, and caused the frenzied rush of diamond-diggers up from the coast, long before the South African main lines were in existence, which laid the foundation of the fortunes of Kimberley. In the neighbourhood of the city we shall see many of the old open diamond mines, as well as the pit-head gear of the newer underground mines.

We get away from Kimberley at 7.2 a.m, and the going now becomes more brisk. The 45 miles from Kimberley to Warrenton are run in 74 minutes, at an average of 36½ m.p.h. Three miles beyond Warrenton, at Fourteen Streams, there diverges an even more important “branch” than any hitherto seen. It goes across the border into Rhodesia, and then north through Vryburg and Mafeking away up to Buluwayo. From there one can go by rail eastward through Salisbury down to Beira, on the east coast of Africa; or northward to the wonderful Victoria Falls, onward through Livingstone to Broken Hill, across into the Belgian Congo to Elisabethville and Bukama - farthest north of all the railways of South Africa and 1,739 miles from Capetown. But our course lies northeast to Johannesburg. We travel onward, stopping at Bloemhof, Harrisburg, Klerksdorp. Potchefstroom, and Randfontein - stages of 58, 60, 29, 29 and 60 miles, covered respectively in 97, 113, 55, 55 and 115 minutes. We left Warrenton at 8.24 a.m, and it is now 3.37 in the afternoon.

4-8-2 (“Mountain”) type Baldwin-built Passenger Locomotive. South African Railways.

Johannesburg is drawing near, and evidences of the industry that has made the great city what it is are now around us on every hand. Great conical hills, like the china-clay mounds of Cornwall, rise for 30 miles on all sides of Johannesburg, along the “Rand”. They are known as cyanide dumps, and consist of the crushed rock, heaped to waste to the tune of two million tons a month, from which has been extracted gold to a total value that now reaches no less than 920 million pounds sterling. Out of the development of this great industry there has arisen the largest and wealthiest town in South Africa, 81 square miles in area, containing over 800 miles of streets and a population of more than 300,000 people. At no great distance away in the Transvaal there are also abundant deposits of coal and iron ore, which between them are establishing an iron and steel industry.

We are once again on a busy stretch of railway. We may well marvel at the size of the wagons used by the South African Railways for the carriage of their heavy mineral traffic. There are no 10-ton four-wheeled wagons to remind us of the “toy” trucks of our own country. There are all-steel bogie hopper wagons, discharging from underneath, and bogie high-sided wagons, emptying themselves from three sets of side-doors in each side; both types are 40 ft in length by 8 ft in width and have a capacity of 100,000 lb, or 45 tons, and a tare weight of 18 tons. Even larger 12-wheeled wagons carrying 67 tons of coal apiece are also in use. Special “specie” vans are employed for carrying the precious freights of gold and diamonds down to the coast. These vans, which are of unusually strong construction, contain safes raised off the floors, so that the armed guards, who travel with every consignment, have a clear view of the safes on all sides. Many other most interesting types of vehicle on the South African Railways will have been seen en route, but there is no space left in which to describe them. We shall not have failed to note that every vehicle, freight vehicles included, is fitted with combined central buffers and couplings, and also - most important in view of the heavy grades traversed - with the automatic vacuum brake.

The last 28 miles from Randfontein require 53 minutes, and at 4.30 in the afternoon of our second day’s journey we roll into Johannesburg. We can go on to the capital city of Pretoria if we like - through carriages are provided in the train to enable us to do so - but we shall have to wait 40 minutes for our connecting train. The additional 45 miles of journey are booked to take 75 minutes, and Pretoria is reached at 6.25 p.m. But at Johannesburg, the head-quarters of the South African Railway administration, the journey of the “Union Express” is at an end. It has covered 1,000 miles - all but a mere 44 - and has risen from sea-level to an altitude of no less than 5,735 ft in the course of the journey. Perhaps the most remarkable of the impressions that will remain with us when the memory of this trip has vanished into the past is that it should have been possible to travel for so great a length of time in such perfect comfort over so narrow a gauge.

The “Union Express” at Johannesburg, with 4-6-2 locomotive. Note the upper-quadrant signals.

[From The Meccano Magazine, August 1928]

You can read more on “The Cape Town to Johannesburg Express”, “Developments in South Africa”, “Progress in Rhodesia” and “South African Electrification” on this website.

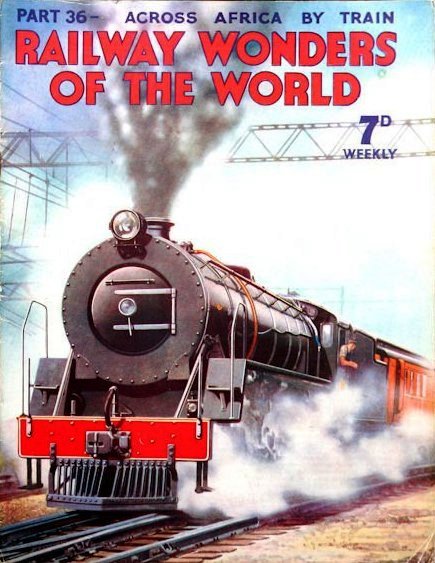

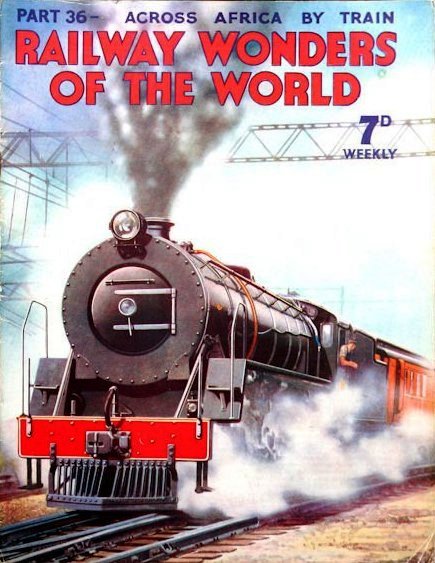

The cover of Part 36 of Railway Wonders of the World featured the “Union Express” leaving Capetown for Johannesburg.

The train is hauled by a 4-8-2 mixed traffic locomotive, built by the North British Locomotive Company Ltd, for the South African Railways.